Friday, June 30

Christ the King Seminary, La Crosse, Wisconsin

For a student who knows what he likes--Baroque, and lots of it--it took me a while to figure out what I wanted to design for my thesis project, the culmination of my studies at the School of Architecture. Some friends of mine had doubtlessly been mentally creating theirs since the moment they arrived at Notre Dame, while others went into the spring semester still a bit hazy on what they planned to do. I figured it out sometime in between, and I remember the day vividly. It was my first real bricks-and-mortar, real-life encounter with the Institute.

I was roadtripping through the hill country of central Wisconsin, thick with vivid fall colors, and had just come back from a serene, silent low Mass and a long, talkative private tour at the splendid German Gothic St. Mary's Oratory in Wausau. I saw the low knobs of hill bright in the sunlight and the wistful ghost of an idea formed in the back of my mind. A little less than a year later, I started prepping for the project. I phoned the North American Superior in Chicago and found him very happy to give me the knowhow to make my imaginary project feel a little more real. A site for the project came via Professor Duncan Stroik, who suggested I consider the area round LaCrosse, Wisconsin, where the Institute's great benefactor Archbishop Burke is in the process of raising the Shrine of Our Lady of Guadalupe. While this project is not connected with the shrine, a site visit arranged by local architect Mike Swinghamer served as a real jolt to the creative process.

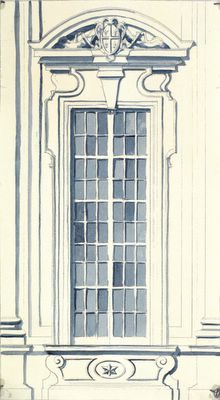

Christ the King Seminary. Valley view. Matthew Alderman. May 2006.

The new seminary stands on an 80-acre site nestled amid the bluffland of La Crosse, looming picturesquely on a long narrow promotory overlooking a thickly forested valley. The complex is divided into two principal parts, the seminary with its classrooms and dormitories, and the chapel and its associated dependencies. The layout of the design is inspired by both seminary models such as the great Roman colleges, and the typologies of the isolated princely abbeys of the German Baroque.

Christ the King Seminary. Window detail, west wing. Matthew Alderman. May 2006.

The geography of the site--as well as the cultural makeup of the area--suggested I look in particular at Melk Abbey in Austria both in terms of plan and ornamentation, while the ultramontane and specifically Tridentine charism of the Institute meant that the architectural vocabulary I would choose should reflect, or at the very least, harmonize, with the great churches of Rome. The result was an interpretation of Baroque drawing on the vigorous muscularity of Juvarra and Rainaldi, the classicism and imperial iconography of Fischer von Erlauch, and the local beaux-arts tradition of nearby Minneapolis exemplified by such minor masters as Emmanuel Masqueray. In using this vocabulary, rich with history and royal iconography, I sought to create in stone a building which would not only form a suitable backdrop for the priestly formation of its inhabitants, but also play a real and active role in that development, through its mirroring of heavenly realities and its ordered disposition.

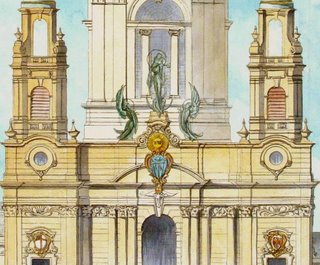

Christ the King Seminary. View of chapel and piazza. Matthew Alderman. May 2006.

The seminary's public face is represented by the entry sequence into the chapel. The spacious oratory, seating over 400, is intended to serve both the seminarians in their public and private worship, and also as an outreach to the local faithful. Given the great interest that has inevitably accompanied the Institute's celebrations of the the Tridentine rite, in addition to the large number of parents and other visitors likely to attend the ordination of new priests and other similar public ceremonies, it struck me as important that the Institute's chapel be grander and more elaborate than most other seminary churches, instead drawing on the typology of the monastic church, in keeping with the Benedictine charism the Institute practices.

Visitors enter up a grand public staircase decorated with images of the patriarchs and prophets, culminating in a fountain representing the Tree of Jesse and a gilded image of the expectant Virgin of the Apocalypse standing on the horns of the moon. The front elevation of the church continues this apocalyptic theme, derived in part from the traditional tympanum iconography of mediaeval churches, but adapted to the Baroque language of the design. At the summit of the church facade is Christ the King seated in judgment, flanked by two angels bearing instruments of the Passion. By passing over this symbolic, eschatological threshold, the pilgrim enters into the eternal world of heaven beyond.

Christ the King Seminary. Longitudinal section through complex. Matthew Alderman. May 2006.

The twin themes of Christ's kingship and Christ's priesthood are threaded together throughout the complex. Crowns, regal stars of David, and other courtly images are common, while Christ the High Priest is referenced through the repeated iconography of the heavenly mass. Throughout the church, angels are shown in liturgical vesture, bearing the instruments of the Passion as the deacons, sub-deacons and acolytes of the eternal liturgy. Rich marbles in strong, masculine, imperial colors predominate--reds, amber-browns, golds and yellows, a palette rich in symbolism derived from Melk and Munich's Assamkirche and reminiscent of the churches of northern Italy.

Christ the King Seminary. Section showing ornamentation of side-chapels. Matthew Alderman. May 2006.

Within the church, six chapels with side altars are dedicated to the order's various patron saints, while the choirstalls for the clergy are placed under the dome, with two galleries above for the pipes of a chancel organ intended to sustain the chant and set pitches. (This arrangement, with the galleries occupying shallow transepts, is derived in part from the local precedent of St. Mary's Basilica in Minneapolis, though domed chancels of various type are not unknown in the German roccoco.) A larger organ with positive is placed in the choirloft over the narthex of the church, for the use of professional choirs and visiting orchestras. The high altar stands in the curve of the apse, a great mass of gilding and golden marble serving as the culminating moment of the entire design. Christ is depicted with arms outstretched in the vestments of the eternal priest, hovering over the altar in silver and gold against a background of gilded mosaic. (In retrospect, the image of Christ the King is perhaps more reminiscent of the so-called "resurrexifix" than I might have liked. But that's one small detail, and the idea remains potent and easily able to be re-cast.)

Christ the King Seminary. Transverse section through chancel showing dome and high altar. Matthew Alderman. May 2006.

The seminary proper is arranged around two primary courtyards. The church's apse is ringed with a series of sizable sacristies designed with the large volume of seminarians and clerical visitors likely to be in attendance during the Divine Office and Mass. The public and private apartments of the rector and vice-rector are located above, allowing some measure of privacy and also the ability to be equally close to guests and professors. A small guest wing, located close to the church for the convenience of visiting prelates, is tucked into the curve of the hill on the east flank of the church. The farther end of the east wing is occupied by classrooms on the first floor, with the second and third floors house the two-room apartments of the professors and priest-students.

Christ the King Seminary. Principal floor. Matthew Alderman. May 2006. (East is approximately at the top).

The west wing, closer to the church, is occupied by the administrative offices of the seminary, while the remainder holds classrooms with four floors of student dormitories, two above and two below. Two transverse wings holding the refectory, a large assemby or chapter hall, and an audience hall for visiting prelates, define the larger seminary and smaller sacristy courts. A sizable public entrance is located on the western side of the seminary, leading to an elegant public staircase, marble hall, and the entrance to the refectory.

Christ the King Seminary. Typical upper floor. Matthew Alderman. May 2006.

This project was a fascinating opportunity to spread awareness of the Institute, to explore a fascinating web of differing functions and needs required by such a complex. The ordered hierarchy of such a structure serves to create a practical environment for the education and formation of future priests, but beyond that, the seminary becomes an icon of the invisible reality of the heavenly Jerusalem--solemn but joyous, ordered but not merciless, splendid but appropriately sober and severe, with beauty given back to the public and austerity provided for the seminarians in their private cells, like a prelate clothed in cloth-of-gold with the rough fiber of a hair shirt underneath. This project is, of course, only hypothetical, but such exercises serve to generate fruitful discussion, and I hope that these explorations may inspire us to demand more in church architecture--to return to an architecture which truly speaks of transcendent realities, of the realm of the King and Sovereign Priest, Jesus Christ the Lord.

It Can Be Done

My major problem with much of the rhetoric in discussions of liturgical music is how theoretical so much of it is. In other words, everything tends to be couched in terms of a dismissal of the status quo and the call for a return to the glories of some halcyon past. Having done some historical research on the Church in America, I can testify that there was no halcyon past. Thomas Day has made invaluable contributions with his books Why Catholics Can't Sing and Where Have You Gone, Michelangelo? both of which describe the trendiness and mediocrity of music in American Catholicism before the Second Vatican Council (sound familiar?). In a certain sense, very little changed but the language and the style.

The problem, then, is both a liturgical and a cultural one. How does one reconcile a liturgical and musical tradition that comes off as very "highbrow" and "arty" with a decidedly middlebrow culture that tends to reject these things, and which furthermore tends to embrace a more emotional form of piety than that typically expressed by the chant and polyphony tradition? In other words, a culture where Amazing Grace has far more cachet than Veni Creator Spiritus.

Certainly, the Church has a glorious musical tradition, but this has almost never been heartily embraced in North America, except in some pockets of the Midwest.

How, then to bring about a positive encounter between this musical tradition, which the Pope has recently re-emphasized, with the state of things on the ground in America? The first important thing to do is not to act like snobs. One of the main obstacles that keeps chant and polyphony out of American churches is the suspicion that this is snobby music that belongs in the concert hall. The primary way to avoid snobbery is to approach the current scene with some level of understanding, both in terms of what motivates people to embrace music of, say, the St. Louis Jesuits, and how to introduce and educate about better music in a charitable fashion.

Another important aspect of this process is to be sensitive about the issue of Latin. Your parish is not going to switch from "Mass of Creation" to a polyphony Mass said entirely in Latin, and it doesn't have to. Suspicion of Latin can be ingrained, and isn't going to go away immediately. Start by emphasizing some of the better recent works by the likes of Richard Proulx and Carroll Andrews, contained best in GIA's Worship III and less so but somewhat adequately in Ritualsong and Gather Comprehensive, Second Edition. Similarly, World Library Publications and OCP are both putting out more and more decent, solid music (even Dan Schutte has gotten in the act and written a beautiful "Song of Mary" arranged for brass and organ). Over time, you can introduce a Latin Agnus Dei, and with the right choir perhaps a performance of the Mozart "Ave Verum Corpus" or a similarly easy motet. This is a way of getting people used to Latin as a viable liturgical tongue and welcoming of more of it. Key to all this, of course is doing it well. A poorly carried off attempt will simply prove embarrassing and further entrench the status quo.

Like the title of my post said, this can be done, and it doesn't have to be done so self-consciously that anyone who doesn't buy completely into the program is going to feel lost and rejected. I present as a model of this the 11:00 a.m. Mass at my own parish, Our Lady of Mount Carmel in Chicago. Our Lady of Mt. Carmel is a beautiful English Gothic church in the East Lakeview section of the north side of Chicago. Here is an example of how our typical Sunday Mass will go:

Opening or Introit Hymn (We have been using some hymns from the wonderful new "Introit Hymns for the Church Year" by Christoph Tietze, From World Library Publications. Tietze has done a wonderful service by setting all the Introits for the year to classic hymn tunes - this is a highly recommended book.)

Choral Kyrie (English or Greek, depending on the setting, which changes each week)

Choral Gloria (usually from the same setting as the Kyrie)

Choral Psalm Setting (we make use of the wonderful in-house settings by late OLMC choir director William Ferris and current director Paul M. French)

Choral Gospel Acclamation Verse

Creed (Spoken in English or Latin Credo III, depending on season)

Offertory Anthem (Usually from the polyphonic or English choral tradition, also including new anthems by the likes of Richard Proulx, Paul French, and Jerome Coller, OSB)

Sanctus/Memorial Acclamation/Amen (Not choral - we rotate between the Proulx setting of the Schubert Mass, the plainchant setting, and the "Danish Amen" Mass)

Choral Agnus Dei (Usually same as Kyrie and Gloria. Usually we chant the first two verses of the Agnus and then sing the third verse from a choral setting. This is highly recommended, especially as a way of convincing pastors a choral setting won't take forever.)

Communion Chant (There is no communion hymn - often times we use the effective method of singing the Latin chant and then recapitulating it in a short English choral interlude before repeating it. Thus, people musically get both the original chant and the translation.)

Communion Motet/Anthem

Closing Hymn

Again, we are able to do all of this within an English Missa Normativa, in a normal, territorial parish. I think Our Lady of Mt. Carmel provides a good example of how to unselfconsciously build a good music program in a normal, young, growing parish. Our congregation consists largely of young professionals and families, and seems to be growing. Thus, it is possible to do all of this and have a full church every Sunday, not full simply of people who are "fans" of this music and ideologically selected but of ordinary parishioners who understand and value it. Thus, it can serve as an effective model for how to move forward from here. Thus, while traditional music can mean an empty church, if it does done poorly, it can be an integral part of a full and thriving parish if done profesionally and charitably.

Thursday, June 29

Wednesday, June 28

This just in!

Pope wants guitars silenced during mass

VATICAN CITY, June 27 (UPI) -- Pope Benedict XVI is calling for an end to guitars and a return to traditional choirs in the Catholic Church.

The recital of mass set to guitars has grown in popularity in Italy and in Spain it has been set to flamenco music, the London Telegraph reported.

"It is possible to modernize holy music," the Pope said, at a concert conducted by Domenico Bartolucci, the director of music at the Sistine Chapel. "But it should not happen outside the traditional path of Gregorian chants or sacred polyphonic choral music."

The Pope's supporters say that the music played during mass is a vital part of the communion between worshippers and God, and that medieval church music creates the correct ambience for perceiving God's mystery, the newspaper said.

But Cardinal Carlo Furno, grand master of the Equestrian Order of the Holy Sepulchre of Jerusalem, said it was "better to have guitars on the altar and rock and roll masses than empty churches."

(HT to my Dad, who emailed this over)

Bartolucci vivat!

Tuesday, June 27

Dr Williams: "Actions have consequences – and actions believed in good faith to be ‘prophetic’ in their radicalism are likely to have costly consequences."

Wow.

News and analysis from The Empty Church:

I predict that ECUSA will not last as a full member of the Anglican Communion past the upcoming Primates' Meeting in February, and that the Network will become the official Anglican province in the USA after the Lambeth Conference in 2008. This is going to be very, very, very messy. It's unclear how this will play out domestically in the next two years. Practically, this is completely uncharted territory; theologically, the orthodox have definitely won.

Monday, June 26

Don Jim reports that the archdiocese of Oristano, Italy, is removing its free-standing altar, which had been installed in the 1960's.

Instead, beginning with the consecration of their new archbishop, Mass will be celebrated ad orientem on the classic High Altar.

Given that Cardinal Ruini, the Vicar of Rome, was present for the consecration, this decision has some added prominence.

Huzzah!

From The Father Brown Stories

"Father Brown is a Philistine," said the smiling Smith.

"I have some sympathy with the tribe," said Father Brown. "A Philistine is only a man who is right without knowing why."

~GKC, "The Song of the Flying Fish," The Secret of Father Brown

The ramifications of the recent unpleasantness in the Episcopal Church continue:

- Parish with highest Average Sunday Attendance leaves ECUSA

- Diocese of Quincy to convene special synod, presumably to do the same

Sunday, June 25

Dining with Dead Jesuits

I doubt anyone notices the linoleum in the front hall of the Culinary Institute of America. It’s vintage turn-of-the-century, green-grey, and marked with four initials in big, blocky Big Man on Campus Letters—it took me a moment to figure out what they were, and then I realized it was AMDG, the motto of the Jesuits. Ad Maiorem Dei Gloriam, to the Greater Glory of God. Students spin past this spot so quickly in a thin, constant, frenetic trickle, they may never even see the letters, much less divine the words they stand for.

It was one of those pale, damp, washed-out wet days in late Spring. The morning had been solemn, mournful and pearl-grey as the rain waxed and waned, the spring green of the rolling hills bright against the vacant white sky.

I was at the CIA—and yes, they really use those initials on all their baseball caps and sweatshirts—for a fancy afternoon meal with my mom, dad and grandmother, a little grace-note to celebrate my graduation before I finally plopped myself down in my New York apartment. It was still raining that afternoon, and the vivid spring greenery of the mountainous uplands of New York State were shrouded in thin, milky mist, the kind of flat blank contrast that turns fall leaves from red to day-glo orange. I was at the CIA and the fact that on the floor of this temple to fresh-faced, can-do-and-a-spring-of-aioli American Epicureanism (there are worse vices), was the foundational text of the Company of Jesus did not surprise me. I’d been properly warned.

The Culinary Institute of America is an immense red-brick barracks of a building looming up on a little hillock on the side of the interstate in a little town called Hyde Park just south of Poughkeepsie. It’s one of those stone-trimmed Colonial Williamsburg-on-steroids deals that were so popular with big institutions back about a century ago. The roofline bristles with verdigrissed cupolas, dormers and belfries, and below are orderly even ranks of mullioned windows. The place is majestic—the words “pile” and “stately” convey some sense of its genial bulk. At the front it’s a massive slab of façade, at the back, it cascades into an open question of descending wings and a long projecting plateau of auditorium that looks, from its apsidal back, strangely like a chapel.

You’d be forgiven if you thought as much. A glance at the handy you-are-here map in the crowded little front foyer indicates the auditorium floorplan suggests nothing so much as a little Counterreformation church with sanctuary and three neat little side chapels per side. It suggests this because, in another life, it was just that. There’s a lonely little IHS that still roosts amid the tromp-l’oeil clouds of the beaux-arts baroque ceiling, and Melchisedek, King of Salem, offers bread and wine against the rain-dulled stained glass as if nothing ever happened.

My friend Dan specializes in figuring out where things go when they’ve been forgotten, especially Catholic things. Naturally, he’s learned a lot about the late sixties as a consequence. Something happened here about then. Statisticians who keep track of this sort of thing report that the high water mark of American Catholicism, in terms of priestly vocations, was not some mystical grey-flannel month in 1950 but 1965, square in the wake of a pastoral Council that happened to convene, through no fault of its own, in the middle of the lurid Age of Aquarius, and a thousand new fads already well-advanced in certain odder and more esoteric sectors of the American church quietly slid into the wings under the stolen flag of Vatican II.

Five years later, in 1970, the Jesuits move out of the seminary of St. Andrews-on-Hudson, with its 150 rooms, its eighty acres of turf, and its presence lamp burning scarlet, for one million dollars and moved their entire novice class into apartments in Manhattan. The province essentially self-destructed shortly thereafter, with their major seminary in Maryland quickly going the way of the dinosaurs.

The CIA occupies the former Jesuit novitiate now; they poured over four millions into the one-million dollar complex. Dan had told me about it before, the result of his part-time scraping of archives and memoirs, sifting through the idle notices that chronicled the spectacular self-immolation of scores of religious orders in that strange era, with its odd yoking of sudden decline and chiliastic optimism.

Do not expect too much of the end of the world—or in this case, the end of history. It always comes back from the grave—whether it’s 1789 or 1989. We can look on those bizarre times from the relative hindsight and comparative security—yes, I dare to use that word, but I’ll take the security I can get—of the eras of John Paul and Benedict, but we’ll never get inside the heads of those on both sides and in the middle, of that age of the dueling magisterium of the Papacy and the anti-magisterium set up by a gaggle of theologians in the wake of Humanae Vitae. All we can do is examine the evidence, and wonder at it.

I stood in the doorframe under the little port-cochere, looking out into the pale murk of the rain and the faded hillscape beyond. The gravelly, concretey piazza was new, the sort of quiet, understated and rather unimaginatively pleasant landscaping that modern architects turn to when they have to work with classicism. There’s an enormous garage below, built into the hillside as it sweeps down to the rain-pocked silver-grey sweep of the Hudson.

It’s quite a place. I’d looked all over the looming institutional-colonial façade for residual Jesuitry, but caught nothing—a few stoical laurel wreaths, stubby, horsey-looking pale green cupolas and beefy ionic columns. It’s a massive brick mill of a building, almost—but not quite—too big for the classical ornament handsomely plastered at quiet intervals across its gigantic façade, and you feel the weight of it press down on you majestically as you move your gaze across it in profile. It is military, and Jesuit, and American without a doubt, Mount Vernon re-imagined on the scale of a German princely abbey, with the curt, no-frills handsomeness that fills so much of the few remnants of emigrant Catholicism that remain in this nation.

The three of us, scooting my wheelchair-bound grandmother under an awkward crown of umbrellas, ducked over to the CIA’s Italian restaurant, a pleasant and cheerily incongruous marigold yellow stucco villa that stands off to one side in the crook of one the arms of the old seminary—now called Roth Hall. It looks like an Olive Garden in the off-parcel of a mall, that is, if one had ever been plopped in the landscaped Tuscan background of one of Mantegna’s Madonnas. A pleasant ironwork sign with a hanging shield displaying three old-fashioned folks fesswise indicates the place’s namesake of Caterina de Medici, the godmother of French cooking and the mythical progenitor of the fork. Inside, there are Medici palle everywhere.

Appetizers came and went, and we luxuriated in the prosciutto and the hot steam of soup as the rain fogged the world beyond our windows at the corner table, and I got to thinking of America’s recent discovery of food. Or cuisine, anyway.

Cooking, of the fancy nouvelle kind, is everywhere these days. You can’t swing a stainless-steel pot without hitting a would-be Emeril or an aspiring Rachael Ray. (Though I am told serious foodies despise Miss Rachael, a bubbly sorority gal of a food guru). Now the fusionists and nouvelle chefs have decided to go native and have given birth in New York to the extravagances of the post-modern fast food industry, where one can find oneself paying eight dollars for a take-out burger. I remember back when people used to talk about Hamburger Helper. Now, even crummy parks service restaurants in Yellowstone put words like aioli on the menu, and everyone knows what tiramisu is. The worst thing is, I actually enjoy it all. I am the worst of gourmet gourmands. But I try to eat my cake and thank God too. That’s the way to take this all in stride, rather than going too Puritan. Catholics, as a friend of mine recently said, are natural sensualists--we just like to keep it all in proportion, and properly ordered with the proper senses.

Part of me welcomes this brave new world Americans have stumbled into, the discovery that there’s more to dinner than such Lutheran delicacies as cream of mushroom casserole, and that Kraft cheese isn’t, really. Good food has always been a hallmark of Catholic civilization, everywhere from Madrid to Vienna. While it is the Protestants who call the Eucharist a meal, it is Catholicism that has an almost mystical reverence for the dinner-table and the cook-fire of the hearth. Civilization, I think, came into flower only after men and women decided they could let down their guards and eat together in peace. The age of TV dinners and fast food has done much to undo that—so I can’t help be happy when anyone wants to bring it back, and with such excellent results. Pass the lemon gnocci in herbed chicken jus, please. Or perhaps, praise God and pass the lemon gnocci, as it’s a very Catholic action, I think.

Or it might have only have that potential, still frustrated. This newfound American love of the gourmet lacks the relaxed energy of the Catholic table—except when it and my family intersects, where we bring in our culture with us like a little picnic basket. Otherwise is too popularized and not popular, too overly-serious and not solemn, too worshipful and yet devoid of divine gratitude, too mingled with the late-twentieth-century equivalents of spirituality and bodily mortification—our fixations with authenticity and weight-loss, the latent results of Yankee Puritanism rising to the surface after a long and troubled sleep. Without the church calendar, we can’t tell when to feast and when to fast, when to eat partridge and when not to, as St. Teresa put it.

(Still, perhaps the slowness of sitdown dinners may yet teach us patience—though the growth of the postmodern fast food industry I mentioned above—only in New York—may prove otherwise.)

I don’t blame the Culinary Institute for any of this. I’d love the place if I was a chef, with its enormous kitchens and warm roaring fires in the rain. To them, food needs to be serious, as art is always a serious and sometimes messy business from the inside. They are turning out artists, and every age needs that luxury as a necessity. I don’t even blame them for taking the great barracks of St. Andrew’s off the hands of the Society of Jesus; somehow the sale of this great barracks seems like a distant natural catastrophe which has lost its ability to shock us as it dissipated through time and space, like the Lisbon earthquake or Krakatoa. Everything in the sixties has that strange shipwreck quality about it when you look back at it today.

(Ironically, the CIA offers what might be the perfect Catholic nerd’s evening out—good food, church architecture, and an opportunity to complain about the post-Conciliar era).

The cooks can’t be expected to understand what happened here—but the Jesuits, even in the misty haze of 1969, purposefully lost something on a scale so grand even they must have realized the shock of what they did. I don’t know if their decision was made with gleeful anger of the past or blind, cheerful optimism, the difference between leaving your mother’s photograph behind when you move house, or flinging it angrily against the wall with a tinkle of glass. Their desire to break with the past, to fling themselves into the abyss of tomorrow made them lose not even the orthodoxy of their past but even a sort of revered private heterodoxy that still draws pilgrims to the place.

Chatting with the waitress as she handed off a steaming and welcome plate of ravioli to me, the girl explained that somewhere in the bowels of the complex, overgrown with new pseudo-classical wings, was the cemetery of the old Jesuit Fathers. They hadn’t moved the graves when they packed up shop.

There’s a certain melancholia here, like the monks interrupted at their prayer by Thomas Cromwell’s men, until you realized there was no forced dissolution here. The bones of their past were left behind like forgotten luggage. They didn’t have time even for the recent liberal past—for one of those graves is the final resting place of Père Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, the ghostly father of so many odd and almost Gnostic turns of phrase. His disciples pop up from time to time and ask to see the old boy.

I don’t know much about Teilhard. I have a vague recollection of a character based off of him cropping up in the margins of Morris West’s Shoes of the Fisherman. I know he was silenced for his fanciful, wrongheaded and apparently rather bizarre speculations. I don’t know whether his error deserves pity, like the neurotic Luther, or scorn, like Simon Magus. He belongs to the menagerie of one of the hazier realms of history, how a Patristics scholar might look at the name of a dim second-century Marcionite he hasn’t heard of.

I have the vague idea his heresy involved Christ’s redemption somehow getting tangled up in future human evolution, finally intersecting with God at the unsettlingly-named Omega Point, a turn of phrase which reminds me nothing so much as a large blob of phosphorescent mint jelly. The few fragments I have seen of his work quoted are as impenetrably pseudo-mystical in a twentieth-century way as anything cranked out by Valentinian or one of the other scribblers of the Gnostic scriptural sausage-factory of the pre-Patristic age. It attempts to be mystical, but not mystagogical—to appear enlightened by saying very little with very much.

His spurious yoking of redemption to biology—if I understand his incorrect ideas correctly—seems less the problem of a cleric or an archaeologist than the sort of odd fringe mysticism common amid science-trusting though unscientific laymen. For a man of faith, or even a man of science—rather than a dabbler in one or both—it is an odd error to profess.

The Jesuits still circulated his scribblings sub rosa in mimeograph form and probably enjoyed soaking up the mild thrill of cloak-and-dagger posing that it entailed, while the man himself appears to have kept fairly quiet in his declining years up at St. Andrew’s, dying on Easter Sunday, 1955. Fifteen years later, the Jesuits that had ooh’d and aaah’d at his theological pyrotechnics left him, and their other predecessors, behind with the cooks.

After dinner, I made my way back to the building’s old chapel, now the principal banquet hall. I walked down the main corridor, past the glass doors of little classrooms festooned with peculiar official names making reference to donations from Wine Spectator and more exotic sources. Instead of a projector screen, the cockpit of the classroom looks like a TV stage kitchen, bright with cheery Italian tile and the warmth of the hearth. Despite the clerical negligence that came out of this, the place is pleasant and even likeable. Perhaps it wouldn’t be so bad to study here, to be a chef. On the other side, glass windows look up onto one of the complex’s numerous restaurant kitchens. A young dark-haired girl in a toque is cutting out pastry slabs from patterns to create an extravagantly medieval pastry in the shape of a castle. Beyond, windows look onto a grey classical cloister, strangely wintery on this humid day.

And the chapel. Over the door is an elaborate coat of arms, perhaps that of the Farquharson who the deconsecrated oratory is now named for. It’s a touch of chivalric levity which I can’t help liking despite the holy image it doubtlessly replaced. Inside, it’s a beautiful space from the waist up, ignoring the prosaic, broken tangle of round tables that littler the nave floor. It’s a memory of that stretch of time a hundred years ago when the world of American Catholicism was not yet monolithically Gothic—when domed Polish basilicas and the fluted pillars of Renaissance Rome were hallmarks of a more complex landscape, artistically and ethnically. Here, the foamy white of beaux-arts baroque, splashed with scarlet and gold, blends with the brick-and-stone colonial America of the exterior.

The high altar is missing, and a banquet table stands now in the empty apse, still gorgeously gilded. Side chapels are now little empty niches filled with spare tables. It is all too clean, too neat and tidy, too well-restored to be melancholy like a ruin. The contrast feels at gut level more baffling than blasphemous. Culinary iconography—a gilded panoply of forks and knives en saltire and busts of patrons and famous chefs—fills in the gaps behind where the altar might have stood. It might have seemed witty anywhere else. But here, in contrast with stained-glass angels and gilded saints, the contrast is strange—and almost unsettling as your eye moves up the pillars, to see gilded mosaics of very different knives and forks, the spears and pincers of the Passion roosting in the vaults above.

Melchisedek is there, like I said, and Ignatius, in black stained glass robes, kneels before a pontiff in a gorgeous Renaissance chamber, as if the hundred rooms of the college were still filled with future SJs. Nobody knew enough Latin to scrape down the slogans of Cibus viatorum and Panis angelicus that stand, with a certain unsettling irony, in the apse. But the apse is empty. You can’t undo what happened in the sixties here. To demand its return after a fair-and-square deal would be futile, and somehow it seems impossible to blame the chefs for this oversight, when there were theologians who knew better to give them this place, once upon a time. It’s an auditorium that looks like a church—while had the Jesuits remained, it might have become a church that looked like an auditorium. But we will never know—and Providence has, for whateve reason, chosen another future for the place.

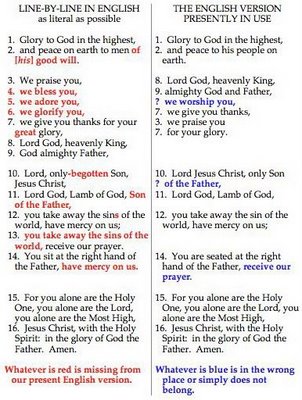

You may be surprised to learn that this is the Gloria:

Image Credit: Fr. Stephanos

While many of us have probably not had the occasion to hear or learn the Gloria as it actually exists, it seems to me that some preliminary exposure will help with the eventual implementation of the new translations...

Saturday, June 24

I have a knack for finding really P.O.D. vintage Catholic paraphanalia, as attested by the half dozen crucifixi, two lithographs of the Sacred Heart, one lithograph of the Holy family, Mary planter, and assorted statues currently housed in my closet for want of a more fitting place to live. All were obtained, I must add, at very attractive prices at second-hand stores throughout the Midwest.

Lucy, however, has me beat. She sends along this picture of her home altar:

Crucifix, $3.00, Episcopalian rummage sale

Madonna, $2.50, St Vincent de Paul

St Joseph Vigil Candle, $1.00, ethnic grocery store

Pictures, 2 color photocopies @ .29, ND Copy Shop

Frames, 2 @ .25, St Vincent de Paul

Rosary dish, .10, St Vincent de Paul

assorted devotionals, .10 each, Loomes/St Vincent de Paul

The statue of Mary and the Crucifix are the most impressive, both vintage plaster. Here's a close-up of the Crucifix of Christ the King Sovereign Priest, a very unusual thing to buy for $3, much less from Episcopalians...

I'm quite pleased with my own home altar, but it was much more expensive. Perhaps in the future, I'll be able to post a picture of it, as well.

Friday, June 23

Thursday, June 22

Annuncio Vobis Gaudium

Habemus Secretarium

(I invite our capable readership to correct the Latin, as I fudged "secretary.")

On the Meaning of a Curious Slur

The feud between "orthodox" and "traditional" Catholics is well known and often (at least from one side) bitter. The feud is as old as Vatican II, certainly, and perhaps one of the Council's least-happy results: in a time which often witnessed the abandonment of Sacred Tradition, those two groups which determined to hold fast to Sacred Tradition were not infrequently at each other's throats.

What, then, is the difference between those who tend to profess themselves "traditionalist" Catholics and those who labell themselves "orthdox" Catholics? Put neutrally, both groups see themselves as holding fast to Sacred Tradition. The "orthodox" Catholics, on the one hand, have continued to cede the right to determine what CONSTITUTES Sacred Tradition to contemporary Church leaders; the "Traditionalist" Catholics, on the other hand, have reserved that right from contemporary bishops, which--in the resulting lack of ecclesial oversight--requires some exercise of their personal judgement in determining what constitutes Sacred Tradition.

This, then, seems to be the long definition of that curious neologism, "Neo-Cath"--a less-then-creative slur used by "Traditionalist" Catholics against their "orthodox" Catholic confreres: the "Neo-Cath" is ridiculed for allowing the continuing hierarchical Church to define the bounds of Sacred Tradition. One might point out that this is rather like St. Ignatius of Loyola, confessing that he "would call black what appeared to be white, if the hierarchical Church so said." (Spiritual Exercises)

Update: Originally, this post linked to the material which inspired it, but I've decided that isn't really necessary, as I've become more curious about exploring what separates "orthodox"--the sort of "orthodox" that might well attend, as I do, the old rite, and are increasingly optomistic about contemporary Catholicism--from "Traditionalists," who have little good to say about contemporary Catholicism.

Tuesday, June 20

Today, I am told, the Episcopal Church's House of Deputies rejected any attempt to apologize to the Anglican Communion for electing actively homosexual bishops and blessing same-sex unions. Rather bold.

The other two Episcopal dioceses which reject women's ordination, Quincy and San Joaquin, are meeting shortly to consider joining Fort Worth's request for alternative primatial oversight.

One well-informed reader emailed:

"It's a good thing the Holy Spirit is protecting the church because the Vatican clearly has no sense of timing. If they acted now, as ultra-conservative Anglo-Catholic dioceses are jumping ship, they could instantly have a robust Anglican Rite."

I know she's right.

And I wish the Vatican would.

But I don't think it will. (heavy sigh)

Monday, June 19

Stop a Church Closing - Help Save St. Vincent's!

The historic New York parish of St. Vincent de Paul down in Chelsea (116 West 24th Street) is facing closure. A recent article in The New York Times focused on the parish's small but vibrant Francophone congregants, but there's a lot more to the story than the church's monthly French Mass.

What the story doesn't say is there is a determined group of laymen who hope to save the parish by bringing a new focus to the parish's mission. While not forgetting the church's special mission to French, Haitian and Francophone African emigrants in Manhattan, these men and women hope to emulate the examples of other parishes such as the Tridentine revival of Chicago's St. John Cantius and St. Gelasius, Opus Dei's work at St. Mary of the Angels, and the work of a number of other urban religious orders in places such as Wilmington. They have thus an interest in inviting to take over the care of the parish either an order not unlike the Institute of Christ the King; like the historically French Vincentians--who have no presence in New York yet; or Opus Dei, already close by at Murray Hill but lacking a parish as such.

The logic of the archdiocese in ordering the parish closed, possibly as early as the end of the month, is dwindling attendance. However, a revitalized St. Vincent's has the potential to be a witness to gentrifying urban professionals and Bohemian artists in a neighborhood increasingly influenced by sex, secularism, and a new age mentality verging on the pagan.

Given the cultural ministry offered by Tridentine orders, or the popularity of Opus Dei among youth looking for structure in a structureless world, such a parish could be a true beacon to the neighborhood and the island as a whole. (Mass would presumably continue in French, though that is part of a much larger picture, even now.) Of course, taking on a parish is a major undertaking for any order, whether small or large. It seems to me that perhaps the parish could be closed for a time, with the potential to be re-opened soon, while funding is undertaken. That being said, unlike St. Mary of the Angels or St. John Cantius, St. Vincent's is still in good working order, a noble structure not unlike La Madeleine in Paris. One hopes that it might become as glorious a beacon as the example of its equally Parisian namesake, the great St. Vincent.

How can you help? At this point, just spread the word. One of the most important things (especially in the case of a Tridentine or otherwise traditionally-oriented parish) is to show that there is a constituency in New York for such things. Chicago has shown that two full-blown Tridentine congregations are capable of existing within the same city. New York does not even have one full-time parish--only the Sunday mass at St. Agnes, and no Latin masses during the week.

The issue, however, is not just Tridentine. The witness of Opus Dei or some other tradition-minded order could prove just as vital to the parish's survival and as a witness for orthodoxy in the neighborhood. St. Vincent's, under the care of any good religious order, would continue to be a presence in a neighborhood with great potential; after all, that the decline of the great urban parishes certainly has done much to change the religious face of the inner city, and will continue to as suburbanites return to the urban core, and find shuttered churches there.

Please write to Mr. Richard Sawicki at rmsawicki@hotmail.com, or to me, if you have anything to say about these plans. I'm not asking for much, just an expression of interest in such a project, or that you might avail yourself of such a parish's services and programs, which have the potential to be virtually unique among New York's numerous parish churches.

The Episcopal Church yesterday elected a female presiding bishop.

This morning, the Episcopal diocese of Ft. Worth, which does not recognize women's ordination, in an emergency meeting this morning, requested alternate primatial oversight:

The Bishop and the Standing Committee of the Episcopal Diocese of Fort Worth appeal in good faith to the Archbishop of Canterbury, the Primates of the Anglican Communion and the Panel of Reference for immediate alternative Primatial oversight and Pastoral Care following the election of Katharine Jefferts Schori as Presiding Bishop of the Episcopal Church.

This action is taken as a cooperative member of the Anglican Communion Network in light of the Windsor Report and its recommendations.

Vote: Unanimous in favor

Because Ft. Worth-Episcopal does not recognize women bishops, it is arguing that it has no primate. Thus, it is seeking oversight from another Anglican province, not the Episcopal

Church-USA (which is the Anglican province of the USA).

As explained to me, this may have interesting implications. If the Diocese of Ft. Worth is given oversight by another province (most likely an African province, or the Archbishop of Canterbury himself), technically it would not be out of communion with the Episcopal Church, because the Episcopal Church at large is in communion with Canterbury which is in communion with Ft. Worth.

But, the new presiding bishop has, apparently, hinted that she might file charges against Ft. Worth for breaking its communion with the Episcopal Church-USA. This is tricky, however, because it could suggest that the Episcopal Church is not in communion with whichsoever primate takes over guidance of Ft. Worth, and, roundaboutly, would suggest the Epsicopal Church isn't in communion with the Anglican Communion.

But, if both the Episcopal Church-USA and the Diocese of Ft. Worth stay in communion with Canterbury, but each under different primates, that amounts to there being two Anglican Provinces operating within the United States: one province which would likely be very traditional, the other which would be... well, Episcopal as we have come to know it.

The opening address of this resolution was pointed out to me as particularly meaningful. The Diocese of Ft. Worth has addressed past concerns to the Archbishop of Canterbury and Panel of Reference, only to have them completely ignored. This time, Ft. Worth has addressed its concerns to all the Anglican Primates as well. Thus, while the Archbishop of Canterbury will ignore the motion and hope that it simply go away, if there are any African primates interested in making a statement to the Episcopal Church-USA, all they would have to do is pipe up, "We'll be your primatial oversight!" ... And, the fireworks.

Interesting. If any primates take Ft. Worth up on the deal, thus creating two operative Anglican provinces with dioceses in the US... very interesting.

As Amy detailed yesterday, the Episcopal Church's General Convention flipped the Anglican Communion the bird by electing, in the midst of its divisive stand on homosexuality and the English Church's debate over women bishops (not to mention the African church's general rejection of women's ordination), a female presiding bishop with no pastoral experience and amazingly progressive theology (thealogy?). Indeed, her diocese has approved same sex union, and has invited Bp. Spong (of "Why Christianity Must Change or Die" fame) to lecture the clergy.

Over the last week, the Archbishops of Canterbury and York, not to mention a few other bishops, gave increasingly and surprisingly strongly-worded warning to the General Convention. The most recent (and blunt) was forwarded to me by an Episcopal friend of mine:

With each English bishop, the message has gotten progressively blunter. It's

hard to imagine how the latest could be any more so:

Bishop Nazir-Ali said that, whatever the outcome, the Americans had already

become detached from the roots of Anglicanism.

"Nobody wants a split, but if you think you have virtually two religions in a

single Church something has got to give sometime," he said.

"Two religions" -- this sort of language is completely unprecedented!! One

expects this sort of thing from +Fort Worth but not an English bishop, and

certainly not one as senior as +Rochester... amazing...

Sunday, June 18

It's always happy to discover an entire thriving congregation of religious of which one was formerly unaware. I'd never heard of the Carmelite Sisters of the Most Sacred Heart of Los Angeles, but things seem to be going well for this congregation of teaching sisters.

"Doctor Gave Me a Pill and I Grew a New Kidney!"

I was never able to decide what I thought of Medjugarie, and I still haven't.

But:

Read Fr. Franklyn's Comment.

I couldn't help but think of Star Trek IV!!!!

Saturday, June 17

Defend your position from Thomas, the Fathers, or the Catechism. I'm pretty curious, and the matter would likely prove definitive of my sacramental theology.

Friday, June 16

DO THE DEW

I plan to spend all today practicing saying "And with your spirit."

Thursday, June 15

Does it really say that??

Yes. Yes it does.

huh.

Speaking of abortion, I was doing some poking around in the Chronicle of Philanthropy, a journal which lists recent charity grants to non-profits. Those bouts of agitation for abortion rights in South America, for example, aren't spontaneously generated: a multi-million dollar lobbyiest industry is consistantly endowed to fight for abortion access is constantly endowed by American foundations.

I am consistently amazed, whenever I read the Chronicle, at the millions of dollars thrown around to support abortion access, especially in Africa. Here were the donations mentioned in this biweekly issue (June 15, 2006).

The Ford Foundation gave:

$2 million to "the International Women's Health Coalition for activities designed to strengthen women's health rights worldwide."

$1 million "to the National Advisory Council on sexual health to promote informed honest dialogue on human sexuality and sexual-health policy in the United States."

$400,000 to ScenariosUSA to "further develop and expand its model creative-writing program, which seeks to expand young people's understanding of their sexuality."

$2 million to "Catholics for a Free Choice for education, outreach, and advocacy programs to advance sexual and reproductive rights."

Apparently, Ford Corporation is doing so well that not only can its Foundation afford to kill off the passengers of its minivans, but they can do without Catholic purchases.

Never will I be ashamed of my Yota again.

Wednesday, June 14

No, No...Not that Father Coughlin, the Other One

Tuesday, June 13

Seen on the Subway

Good name in man and woman, dear my lord,My question is, is this intended to dissuade pickpockets, or console the newly-mugged? Or, in light of the reference to Iago's stealable man's European carry-all, suggest while he may have been a louse, he was louse who was very secure in his masculine identity?

Is the immediate jewel of their souls:

Who steals my purse steals trash; ’t is something, nothing;

’T was mine, ’t is his, and has been slave to thousands;

But he that filches from me my good name

Robs me of that which not enriches him

And makes me poor indeed.

Monday, June 12

I give up. Life is too weird to parody anymore.

If someone ever wants to do me a really big favor, set up a parish consort of racketts, bajones, cornamuses, sackbutts and other brass and oddball woodwind instruments and have them accompany the music of the Counter-Reformation the way it was often heard, at least outside of the Sistine Chapel--with proper accompaniment, or if that won't work, just a few falsobordones in between chant verses. It's just it's about time someone recognized there's more out there than just unaccompanied polyphony, even if that is the preferred, Pius X-tested, Pius X-approved style.

More on St. Saviour's

The church is predominantly red brick with stone trim with a green copper dome and a dark slate or shingle roof behind the parapet. White-painted metal moldings, cornices and other details could be used on the upper portions to save on costs, as at All Saints. The key to a church like this is to save your money for the big moments--brick on the sides and a largely stone front, or even just a few nice stone details and statuary, is a wise use of funds, so as to save up extra cash for the interior, particularly the sanctuary and altar.

The church is predominantly red brick with stone trim with a green copper dome and a dark slate or shingle roof behind the parapet. White-painted metal moldings, cornices and other details could be used on the upper portions to save on costs, as at All Saints. The key to a church like this is to save your money for the big moments--brick on the sides and a largely stone front, or even just a few nice stone details and statuary, is a wise use of funds, so as to save up extra cash for the interior, particularly the sanctuary and altar. The interior is mostly plasterwork--another cost-saving measure. Borromini was famous for his Baroque-on-a-budget plaster interiors, many of which are considered jewels of world architecture today. True baroque does not always require the extensive stonework that many Gothic churches present--while degraded by some as structurally a sham, it's actually much more manageable by current building standards and opens up the field to a whole range of exciting possibilities in regard to vaulting, domes and decoration.

The interior is mostly plasterwork--another cost-saving measure. Borromini was famous for his Baroque-on-a-budget plaster interiors, many of which are considered jewels of world architecture today. True baroque does not always require the extensive stonework that many Gothic churches present--while degraded by some as structurally a sham, it's actually much more manageable by current building standards and opens up the field to a whole range of exciting possibilities in regard to vaulting, domes and decoration.  I was inspired by Borromini's Propaganda Fide chapel in this particular example, in addition to the Wren churches that had given me so many ideas for the parent project. There are room for confessionals, pulpit, choir organ gallery and rear organ gallery, and a fairly broad antiphonal choir beneath the dome in what might be called a "false transept" arrangement which I derive from a very intriguing church in Minneapolis, the late 19th century basilica of St. Mary's. A full-blown set of transepts would have added a great deal more to the budget, while here the cruciform plan is iconographically present on the exterior and on the interior is used to create the practical space always at a premium in small churches, not to mention the sacred distance a long chancel affords, something else hard to manage in small parishes.

I was inspired by Borromini's Propaganda Fide chapel in this particular example, in addition to the Wren churches that had given me so many ideas for the parent project. There are room for confessionals, pulpit, choir organ gallery and rear organ gallery, and a fairly broad antiphonal choir beneath the dome in what might be called a "false transept" arrangement which I derive from a very intriguing church in Minneapolis, the late 19th century basilica of St. Mary's. A full-blown set of transepts would have added a great deal more to the budget, while here the cruciform plan is iconographically present on the exterior and on the interior is used to create the practical space always at a premium in small churches, not to mention the sacred distance a long chancel affords, something else hard to manage in small parishes.  Some classical or baroque parish designs have been cricitized as too expensive, too ornate, or not 'Catholic' enough in comparison with the Gothic. Baroque is undoubtedly a Catholic style, developed in the context of Papal Rome--and while it may draw on pagan classical roots, one could make that argument about many fine things in Catholic culture, or for that matter, the Pope's title of Pontifex Maximus, and it will be a sad day if we wish to throw that most Catholic of titles out! This is I think a manageable, cost-conscious design, and it shows that such a humbler project is possible within the bounds of this manner of architecture, and that given current lack of certain specialty skills, it may be possible, using Baroque-inspired classicism, to achieve a more robust and fuller range of expression with less money.

Some classical or baroque parish designs have been cricitized as too expensive, too ornate, or not 'Catholic' enough in comparison with the Gothic. Baroque is undoubtedly a Catholic style, developed in the context of Papal Rome--and while it may draw on pagan classical roots, one could make that argument about many fine things in Catholic culture, or for that matter, the Pope's title of Pontifex Maximus, and it will be a sad day if we wish to throw that most Catholic of titles out! This is I think a manageable, cost-conscious design, and it shows that such a humbler project is possible within the bounds of this manner of architecture, and that given current lack of certain specialty skills, it may be possible, using Baroque-inspired classicism, to achieve a more robust and fuller range of expression with less money.Still Calling New York Catholic Nerds!

Sunday, June 11

Honestly, the more I reflect on the Christian Tradition and the Scriptures, not only the more confirmed am I in the Catholic articulation of the Faith, but the more completely untenable do I find classical Protestantism. I can remember being rattled by Bible-Bangers assuredly declaring that "a sin is a sin is a sin," no sin being worse for your relationship with God than any other, and no sin being fatal to that relationship. Insert denounciation of Catholic "mortal sins" vs. "venial sins" here.

Really, that rattled me. Then I read stuff like this, and it makes me mad not only that they haven't digested entire books of Scripture.

1 John 5:16-18

- If anyone sees his brother sinning, if the sin is not deadly, he should pray to God and he will give him life. This is only for those whose sin is not deadly. There is such a thing as deadly sin, about which I do not say that you should pray. All wrongdoing is sin, but there is sin that is not deadly. We know that no one begotten by God sins; but the one begotten by God he protects, and the evil one cannot touch him.

Our Lady, Queen of the English Martyrs

Images © 2006 Matthew Alderman.

[My hypothetical project for an Anglican Use Parish in Chicago is old news to our repeat readers, but I thought it would be of interest nonetheless as it's the most complete presentation I've made of the complex so far, as well as allowing to display a number of higher-quality photos and details of the design. Once again, many thanks to Joe Blake and the Anglican Use Society for their interest in my work, and for the many kind words I received from conference attendees. One new addition is a smaller more economical 300-seat version of the project intended for a suburban site, appended at the end of the article. I hope to post a few more of my sketches for this variant in the near future.]

One hundred years ago, the United States was reaping the fruits of a golden age of ecclesiastical architecture. Gothic masters such as the Anglican Ralph Adams Cram threw off the dominant American paradigm of the meeting-house, and replaced it with the ideal of the church, not a lecture-hall but the home of the Real Presence, the icon of the city of God. Likewise, today, many have begun to re-consider the choices of the sixties, and like Cram, raise the cry for an architecture that expresses the transcendence of the Incarnate God and the fullness of our two-thousand-year-old Christian tradition.

As a graduate of the School of Architecture at the University of Notre Dame, I’m no stranger to this debate. The School trains its students to work within the ancient tradition of western architecture—not as mere copyists, but as inheritors of and innovators within this heritage. In Fall of 2005, I designed Our Lady, Queen of the English Martyrs, a hypothetical Chicago parish church and center under the tutelage of Professor Thomas Gordon Smith, one of the acknowledged leaders in the return to tradition in church architecture. We were given a refresher course in the orders of Roman and Greek architecture, as well as a mini-retreat given by a Benedictine priest and chant scholar. We were charged to see the church not as a multi-purpose hall, but as the temple of God, an ideal seemingly forgotten today.

The tragedy of this loss was thrown into stark relief by the parish’s hypothetical site in Chicago. We were replacing the 1997 parish church of Old St. Mary’s, a “progressive” structure designed to look like watered-down imitation of the modernism of nearly half-a-century ago. It feels less like a place of eschatological grandeur in the presence of God than a frighteningly clean airport concourse. Admitted, there’s some iconography, like the walk-through womb-shaped baptismal font, which prompted a female classmate to remark that the only thing she needed to be womb-shaped was inside of her and she hoped it stayed that way.

Still, the parish conducts a lively ministry to the area’s growing population of young professionals. The church looks poised to partake in a general revival of the neighborhood. A majestic parish church in the great Chicago building tradition would have done wonders as a reminder of God’s majesty in this bustling place which sometimes seems too busy to pray. The existing complex doesn’t even try. The site was hemmed in on three sides by a disused raised rail line, an apartment block, and a narrow back alley. Any parish complex which would rise there would risk being a house of God dwarfed by the high-rises of the city of man. We also had to find a way to cram in a parish hall, offices, a rectory and, if we could rise to the occasion, a parish school.

You may wonder, with all this to distract me, how I had time to bring in the Anglican Use. I’ve followed the Pastoral Provision for some time now, and this project struck me as perfect opportunity to explore its rich tradition further. In an age struggling to understand the true meaning of the Second Vatican Council, the Anglican Use is undoubtedly one of the most precious fruits of its commitment to ecumenism, neither losing Catholic Romanitas or the cultural treasures of the Anglican heritage.

As a cradle Catholic, I can’t speak of the conversion experience, but the Anglican Use shows me the relevance of English-speaking culture to Rome. The Anglican Use brings with it a comprehensive liturgical integration of art, music and architecture spiritually similar to the grandeur of Continental Catholicism. Here, this heritage was unfortunately stunted by the battle-zone conditions of American Catholicism, with the fortunate exceptions of a few happy pockets where ethnic tradition still holds sway.

But how could I embody in my design the specificity of the Anglican Use within the universality of the Catholic Church? What style should it be in? Gothic, with its stained glass and medieval piety would seem the most logical choice. But, as you can see, I did not design a Gothic church. Don’t get me wrong. I’m a great supporter of Gothic, and have a great fondness for some of the new Gothic churches that have been built in recent years, such as Our Lady of Walsingham and Our Lady of the Atonement. Professor Smith, who is a man of catholic tastes, would have been quite happy for me to design Chicago’s answer to King’s College Chapel. However, in light that I had the opportunity to work under the tutelage of Professor Smith, a classicist and an enthusiast of the rigorous ingenuity of the Roman Baroque, I decided to start with the unique Anglican Baroque of Sir Christopher Wren and create an idiom both English and Catholic.

Before the Reformation, English Catholicism possessed unique liturgical and artistic tradition in the form of the Sarum Rite. I began to wonder what English Catholic architecture might have become had the Reformation never occurred, and its culture had remained tapped into the Continental mainstream. Baroque, the favored style of post-Reformation Catholicism, does not just mean a building plastered with ornament, any more than Gothic is only about spiky finials. It derives its inner logic from a sophisticated geometry of curves and counter-curves and the concetto, a symbolic concept expressed iconographically through the whole design. A building becomes an expression of a vast spiritual idea that crosses the boundaries of different artistic media and touches the soul, engages the intellect, and delights the senses.

While English Baroque is predominantly a palace architecture, its greatest monument is a cathedral, Sir Christopher Wren’s immense St. Paul’s, and a number of London’s post-fire city churches were built in this style by Nicholas Hawksmoor and James Gibbs. Still, the theology they embody is not as explicitly Catholic as the Anglican Gothic churches of a century-and-a-half later. How to make that Catholicity more apparent? I started sketching. Architecturally, the simple muscularity of English Baroque could be given a Catholic twist. English Baroque is predominantly a two-dimensional architecture of applied ornament; I sought to bring it into three dimensions with the sculptural, incarnational vigor of Rome.

I also discovered I wasn’t the first person to tackle this problem. The masterwork of the Edwardian architect Sir Edwin Lutyens’s career was Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral, a vast structure that blended Wren, St. Peter’s, and Hagia Sophia, while his follower H.A.N. Mead designed Catholic and Anglican Cathedrals for New Delhi that partook of this same spirit. Around the same time, the church-furnisher and artist Martin Travers provided designs for Anglican churches which mingled Continental Baroque with an authentically English, even medieval sensibility, which appealed to my Gothic streak.

But back to the parish. Let’s pay it a visit.

Our Lady, Queen of the English Martyrs is a city parish in the grand Chicago architectural tradition. Perhaps our first glimpse of it comes while walking down South Michigan Avenue, or maybe we catch sight of its green copper dome from some distant overpass. On the outskirts, Chicago is a city of spires looming over a great sea of little roofs, a graceful and European sight. It’s a hot summer day, let’s say. The church’s strong silhouette dominates the skyline, holding its own against the fifteen- and twenty-storey apartment blocks that have begun to sprout up around it.

The afternoon light momentarily transfixes the windows of the immense lantern, the dome moving in perspective above and behind twin bell-towers. Sculpted crowns and martyrs’ palm-branches in relief cluster beneath the cornice, while the strong massing of the façade casts deep shadows on the honey-colored stone.

The church rises majestically out of the void created by the low-lying classical outline of the parish plant. This complex contains a rectory, a parish hall, offices, a nursery and a K-8 school for 500 students including library, dining hall, rooftop playground and underground gym.

Between the twin bell-towers stands a copper image of the church’s patroness, Our Lady, Queen of the English Martyrs flanked by two angels. I wanted to dedicate the parish to Our Lady of Walsingham, but I also wanted to include the numberless English martyrs of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, St. Thomas More, St. John Fisher, St. Margaret Clitheroe, and others, as well as those of the early centuries of English Catholicism—the soldier-saint Alban, or the slain kings Edmund and Kenelm. She holds in one hand the lily of Walsingham, while the Christ Child bears the nails and crown of His Passion.

The façade also features the insignia of the Trinity—the sacred Hebrew initials of the Tetragrammaton, the dove of the Holy Ghost, and the Arma Christi—the instruments of Christ’s Passion arranged in heraldic fashion. On either side are the insignias of the Anglican Use—the St. George’s cross with keys of St. Peter—and the phoenix of the Chicago Archdiocese. The Corinthian order of columns with their flowering acanthus-leaf capitals commemorate the maidenly and queenly strength of the Virgin for whom the church is named. The dome bears the insignias of the four evangelists, while its lofty needle gives the Baroque structure a Gothic verticality reaching upwards to heaven.

Entering through the central doors, we pass through the narthex. On the left-hand side we glimpse the baptistery behind a wrought-iron screen. The octagonal font is covered by a massive wooden lid, inspired by Gothic precedents, but given a baroque articulation which calls to mind the church’s dome. The simple lines of the domed chamber suggest a sepulcher, in which we are reborn in Christ. The baptistery, like the rest of the church, is faced with carved grey stone, highlighting the gilding of font that stand in its midst. Its placement—open to narthex and the south aisle—recalls both the baptistery of Roman tradition, and the English custom of placing a font in a side-aisle. Images of St. John the Baptist and the early English martyrs make the chapel’s significance even more apparent.

Our eyes have begun to adjust to the darkness from the hot bright light of the Midwestern summer. The church’s nave is faced in pale grey stone, set off by bursts of ornamentation in the Corinthian capitals and the richly-colored polychromy of wooden side-altars. Votive candles glow in the shadows of the side-aisles. Everything is suffused by the mysterious blue glow of stained-glass windows far overhead.

The church’s plan is a Greek, equal-armed cross, seating around 500. Tather than being pushed so far back to be invisible from the street, the central dome is visible from the street. It is also an appropriate response to the comparatively shallow depth of the site, which would have made a more conventional plan difficult to achieve. We move up the center of the nave, and through the iconography, move forward in time. In the side chapels, are confessionals set into the wall below enshrined images of St. Austin of Canterbury and St. Gregory—recalling the early missionary roots of the English, their ancient fealty to Rome, and the cleansing power of the keys which binds and looses. We come to the crossing, looking up to the great dome where vast slants of light fall on the richly-carved stonework. In the right transept chapel stands the Altar of the Lord’s Death, a massive wooden side-shrine with folding wings, mingling baroque and Gothic traditions in its shape and iconography.

Its dedication recalls the name of a chapel that stood near the great shrine of Walsingham in the Middle Ages. Its iconography recalls the medieval tradition of the Mass of St. Gregory and the Man of Sorrows, showing a wounded, suffering Christ surrounded by the instruments of His torture—spear, sponge, nails, whips, thorns. On each of the tryptich’s wings, as we pass from the age of St. Augustine to that of the persecutions, stand images of six of the English Martyrs. Through a grille nearby we glimpse more stained-glass blue and catch just a hint of the Lady Chapel beyond, which serves the community as its daily mass and adoration chapel.

And before us is the high altar. Standing distantly in the curve of the apse it is a restrained crescendo of gilding, wood and polychromy against the rich, grey stonework. It has always been before us ever since we set forth in the church, gold leaf distantly winking in the glow of the red-glassed Presence Lamp with its adoring brass angels and martyrial crown. On the left hand a small chancel organ looms above the rich dark wood of three ranks of choirstalls. Following English custom, there stands antiphonal choir between the crossing and the high altar, placed against a reredos as customary in the Anglican Use. The depth of the chancel allows a certain necessary sacred distance to be placed between congregation and celebrant, compensating for the lack of procession possible in a centralized plan. A rood-beam marks the dividing line between chancel and nave, a threshold to heaven marked by the glorious sacrifice of the Cross.

The twisted columns of the uppermost register are a common symbol of the Temple of Solomon—and thus the Holy of Holies, and can be found both in English and Continental Baroque. They flank an image of the Trinity, the Throne of Grace, showing the Father enthroned and bearing the crucified Christ in His arms. On either hand stand two angels in the albs, amices and cinctures of medieval acolytes, one holding the ever-turning sword of flame from the Book of Genesis, the other bearing the burning, cleansing coal of the Prophet Ezekiel. The one wards off the unrepentant sinner from the presence of God on earth, the other beckons to the penitent to come and be healed through penance, absolution and then Holy Communion. The lower register of columns flank the effigies of Our Lady, Queen of the English Martyrs and Saints John Fisher and Thomas More. With their common background of swirling heavenly clouds, the reredos becomes the altar-as-triumphal arch, as window, the place where heaven is opened up and God’s grace pours to earth.

Over the altar, surrounded by a sunburst and standing on the upturned horns of the moon, as the Apocalyptic Woman Clothed with the Sun, is the Virgin herself, bearing up the Christ-Child. Inspired by both baroque and Gothic images of the Virgin, I sought to give her a bearing both maidenly and regal, conveying her inner sanctity with outward beauty, and a face both smiling and yet bearing a secret trace of the bitterness of her Son’s sacrifice. Her vesture is scarlet and gold, colors both sacrificial and royal, and she also bears the ermine of kingship. As with the image crowning the church’s façade, she bears up the Christ Child with the crown of thorns and Passion nails in a cruciform posture that recalls His crucifixion, as well as the golden lily of the Virgin of Walsingham.

[I've been more than a little amused by the remarkable range of reactions this image of Our Lady has generated. A number of people think she's a little too glamorous, a little too pale and European, while others have absolutely loved it, and still others have seen in her gaze a mixture of majesty and sorrow. I understanmd the criticisms, they're valid, and I appreciate the comments. She's sort of stuck with the informal name Cover-Girl Mary as a consequence; one of the funniest comments I got said that she looks like a design for the old Ballets Russes...assuming they ever did a piece called Notre-Dame des Réactionnaires. Yes, she is a bit younger and prettier than some Madonnas, especially the bland plaster variety--though no more conventionally good-looking in relation to the standards of the era than the gilt-haired Schöne Madonnas of medieval Germany. I admit trying to blend Gothic and Baroque via Art Nouveau was perhaps a bit experimental. Still, I rather like her. I also know in the future it'll be my client, and not me, that'll be calling the shots.]

The themes of reunion and of Marian devotion continue in the Lady Chapel we have briefly seen before, dedicated to Our Lady of Walsingham, while a side-altar is dedicated to the martyr Margaret Clitheroe. The Lady Chapel was designed to serve also as a daily Mass and Adoration chapel with three confessionals and access from an outdoor parking-lot when the remainder of the church is locked, saving on maintenance and the onerous demands of heating a Chicago church in the winter.

Turning our attention from the church to the parish complex, covered access from one of the transepts to the Parish Hall and the school above allow access in winter, while parents can drop off their kids at the front lobby safely under the eye of the front desk. On the ground floor are housed the parish offices. On the right side of the church is the smaller Rectory block with room for several clergy and guest apartments and common rooms, as well as a small office for housekeeping staff. I briefly considered including larger apartments for married clergy, though after inquiry discovered that probably offsite housing would be more tenable.

Our Lady, Queen of the English Martyrs has been for me a fascinating exploration of the relevance of Rome to English-speaking Catholicism, and of English-speaking Catholicism to Rome. I hope it may serve to make us demand the beauty that God's house deserves from our architects, artists and church builders, as we step into this new century.