Tuesday, June 30

New Illustration: The St. Bernard Triptych, Part II

Matthew Alderman. S. Bernard of Clairvaux. Ink. June 2009. Private Collection, New York City.

Above his head, two angels bear the coat of arms of the Cistercian Order, while below, St. Bernard bears his crozier in his right hand, the abbatial veil curling around its shaft. His posture is derived in part from Zurbarán's marvelous painting of St. Francis upright in the tomb (ca. 1630/34). Numerous smaller details depict the saint's various attributes in discrete ways--the bees worked into the foliage of his crozier-head, representing his title of Doctor Melifluus; the arms of the Templar Order, whose rule he wrote, on the knob of its staff; another shield depicting the mitres of the three dioceses he rejected; an angel presenting him with a model of the abbey of Clairvaux, and a scroll inscribed with the opening passage of the Canticle of Canticles, on which he frequently preached.

For those of you who missed it, the first installment of this series can be found here. Tomorrow I will share the final panel in the sequence, depicting Christ's revelation of the Holy Shoulder to the saint.

A random touch of architecture: these golden onion domes crown the collection of chapels known as the Terem Churches in the Moscow Kremlin. The cross springing from the crescent, I am told, is said to represent Christ issuing from the womb of the Virgin.

Food Fights as Apologetics

Lifestyles of the Rich and Clerical

One of our readers was curious about the painting of the laughing cardinal I posted Monday. I'm not sure who the artist was, or even where I ran across it online, but it's an example of a curious subgenre popular in the 19th century showing richly-dressed churchmen lounging about in equally opulent interiors. (The example above is by the Frenchman Georges Croegaert). In some cases, there's a touch of the absurd to them, such as one I ran across of a rather tubby cardinal in scarlet choir cassock fishing off the side of a bucolic riverbank. (Though considering cardinals often wore the sacred purple to the opera before Garibaldi put the papal court in mourning, this is, while weird, less weird than one might suppose.) There is probably a touch of anti-clericalism to such rollicking depictions of the clergy, especially given the excess of ormolu that crouds the background, though nearly all the examples I've seen tend towards a low-grade, rather sympathetic view of their subjects. I suppose such satires only maintain their bite of if one assumes that the sacred priesthood must always be ashes and frowns.

Here are a few of the more entertaining examples of the species I've found trawling the web. The following are by Bernard Louis Borione, a French academic painter who was particularly associated with the theme.

Another example of the style by a different artist, Leo Herrmann.

Bertram Goodhue's handsome design for a bishop's throne for the unbuilt Los Angeles Episcopal Cathedral.

Monday, June 29

New Illustration: The St. Bernard Triptych, Part I

Matthew Alderman. S. Bernard Healed by the Virgin.

Ink. June 2009. Private Collection, New York City.

This image is derived from an event described in St. Bernard of Clairvaux: Oracle of the Twelfth Century by the Abbé Maria Theodor Ratisbonne, a convert and the brother of the more famous fellow-convert Alphonse Ratisbonne:

One day, however, his [St. Bernard's] sufferings became so excessive that, no longer able to bear up against them, he called two of his brethren and begged them to go to the church and ask some relief of God. The brethren, touched with compassion, prostrated themselves before the altar, and prayed with great abundance of tears. During this time, Bernard had a vision which ravished him with delight. The Virgin Mary, accompanied by St. Lawrence and St. Benedict, under whose invocation he had consecrated the two side altars of his church, appeared to the sick man. "The serenity of their faces," says William of St. Thierry, "seemed the expression of the perfect peace which surrounds them in Heaven." They manifested themselves so distinctly to the servant of God that he recognized them as soon as they entered his cell. The Virgin Mary, as well as the two saints, touched with their sacred hands the parts of Bernard's body where the pain was most acute; and, by this holy touch, he was immediately delivered from his malady; and the saliva which till then had been flowing from his mouth in a continuous stream ceased at the same time.I used this commission, in part, to experiment with some stylistic elements derived from the work of the Irish stained glass designer Harry Clarke, whose work has appeared here in the past. The edging of sea-shells along the Virgin's cloak is partially inspired by Clarke's work, and also refers specifically to St. Bernard's devotion to the Virgin as Star of the Sea; the saint is thought to be the first to have invoked the Virgin under this title. The star motif on the Virgin's morse also recalls this. St. Bernard and St. Lawrence are visible in the background, with the ill saint curled up at the bottom of the panel.

Tomorrow, I will post an image of the central panel, showing the saint surrounded by his attributes.

An Early Instance of Inculturation, circa 1492

--Henry Kamen, Empire: How Spain Became a World Power, 1492-1763, p. 20.

Scrounging for the Sacred

However, the matter came back to mind when I ran cross a nice little post on the First Things "First Thoughts" blog, linking the cult of celebrity that explains Jackson--and Princess Di, and La Hilton, and all the rest--with the curious case of "Saint" Guinefort, a valiant greyhound who defending a child from a snake, and got killed by his master for his trouble. The animal somehow managed to acquire a sort of popular, unapproved folk-cultus after death, until a local Dominican put a stop to this charmingly sentimental nonsense.

Popular devotion, it must be admitted, has netted quite a few great saints in its time--nearly everyone in the martyrology who lived before the turn of the last millenium owes his halo to a popular canonization that persisted due to the Chestertonian democracy of the dead, but such hauls also frequently included a lot of very odd and eminently forgettable people: some who were quite pious, if probably fictional, such as the baby Rumwold, who preached a sermon after his baptism and promptly died; Muirghein, who was turned into a mermaid for 600 years and appears to be a figment of Celtic imagination; or Josaphat, who appears to be a thinly-Christianized version of Buddha (considering some Buddhist sects appropriated the imagery of Christ on a white horse from Revelation, it's a fair trade).

Others were not so holy. The "martyr" Gotteshalk was killed in battle, and San Simon de Guatemala (a relatively rare instance of a post-medieval popular cultus) was actually a French revolutionary. And some, we've not got a clue. St. Amadour was some guy whose body they found quite randomly; admittedly incorrupt, but one does wonder.

For all our talk of romantic decentralization in the early Church, it's a good thing infallible Rome took over the process during the Middle Ages to make sure all the i's were dotted and t's crossed. (That being said, I am not letting Rome off the hook for crossing Sts. Ursula, Catherine, Barbara, et al., off the list, because a) being absurdly beautiful princesses holding all sorts b) given their veneration has stood at the heart of Christendom for ages, unlike some marginal greyhound or garbled French philosopher, we can be assured that someone upstairs was picking up the phone when we pray to them even if it might be a wrong number. But Catherine's Catherine and a three-day-old talking baby is another.)

We see some of this indiscriminate, if heartfelt, scrounging for the sacred, in today's cult of celebrity, as well. And in it, a lost opportunity for us, as Richard Scott Nokes notes in his piece:

In both cases, the cults were propelled by two engines: the ignorance of the people, and the desire to venerate. As with the angels, we are created as creatures of praise. We seem to be hardwired to praise something, to worship anything. Just as we will eat rotten food and filthy water if no healthy food and clean water are available, we will venerate dogs and celebrities if we see no truly worthy objects of veneration before us.Once again, everything can be a call to conversion. Let's not blow it again, this time.

Etienne’s effort to stamp out the cult of Guinefort failed because he did not address the need of the people to venerate. Their impulse was good; it was simply directed at the wrong object and without providing a new object for veneration, Etienne was dooming the people of Sandrans to eventually drift back to their old ways.

It does the Church little good to cluck and shake our heads at the dismaying display of veneration for Michael Jackson, for in truth he is a martyr, a martyr to our culture’s true god: Celebrity. If we simply cut down Celebrity’s Asherah poles—John & Kate, Paris Hilton, Barack Obama—we leave the job half-completed, ensuring new idols will spring up in their place. If we take away rotten food and filthy water, we must replace it with healthy meat and milk. The worship of false saints, be they greyhounds or pop stars, needs to be replaced by the worship of the Lord. As the Philistines found with their idol Dagon, false idols cannot stand in the face of the one true Lord (1 Sam 5:2-5).

Wherever the Catholic Sun Doth Shine

A fine piece of liturgical illustration, showing the distinctive style of the Belgian journal Bulletin Paroissal Liturgique published in the twenties, and an inspiration for my own work.

Sunday, June 28

Traditional Venetian Entertainments

"Such as pushing one another off bridges, a popular team sport and tourist attraction in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Two rival factions, the Nicollotti (in the black hats), who occupied the half of Venice nearest the mainland and were mostly fisherman, and the Castellani (in the red hats), who occupied the parts towards the lagoon and mostly worked at the Arsenal, would amass in groups on opposing sides of a small bridge and go at one another with baboo staffs until weapons were outlawed and fists substituted. As the bridges at the time lacked parapets, people kept tumbling over, and someone always put a damper on the fun by getting bludgeoned to death. The state vacillated between trying to control these events, and in 1574, proudly featuring a bridge battle as part of its VIP treatment for a visiting dignitary, Henry III of Poland, who was taking a memorable detour on his way to becoming King of France. This fight was not a success, as the king's reaction was to ask them to please stop that, right now. Bridge fights were banned altogether on Saint Girolamo [Jerome]'s Day in 1705, when the factions were going at it so intently that nobody wanted to leave to put out the fire at Saint Girolamo's convent church, which was thus destroyed from neglect on its very own saint's day."

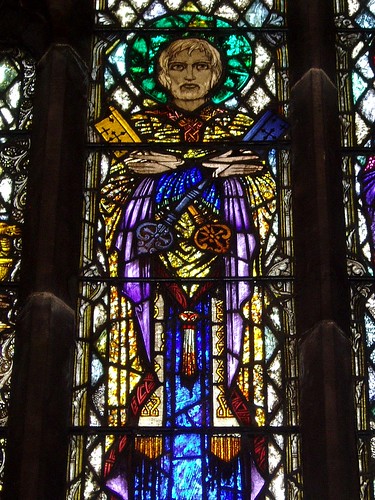

Harry Clarke, Ireland's Master of Stained Glass

Due to an offhand reference by Fr. Symondson, the noted Jesuit who needs no introduction here, I discovered some time back the incredible oevre of the Irish stained glass designer and illustrator Harry Clarke. Curiously enough, I had already stumbled onto one of his best works on a previous trip to Ireland, a suite of stained-glass windows for a convent chapel in Dingle, and promptly forgotten about them. (The docent claimed Clarke could not draft an ear properly, so he covered them with drooping sidelocks, something manifestly untrue when his other work is studied in detail.)

Clarke was a brilliant, tragically shortlived fin de siècle workaholic whose designs are often simultaneously extremely iconographic and also bold, strikingly original and even mildly unsettling at times. (His illustrations for Poe's Tales of Mystery and Imagination are still, unsurprisingly, in print.) Nonetheless, he is one of the few artists of the past hundred years who managed to take the best out of the art of his contemporaries and bring it, somewhat purified, into a well-thought-out and elegantly-designed liturgical context that is exceptionally rich with symbolism at all levels of his design. (Who else could slip a reference to Klimt into an image of St. Brendan, and still make it work?) The iconography is, mostly, quite traditional, but often approached from unusual and affective angles: his stunning redheaded St. Gobnait, is quite conventionally liturgical, but draws on the work of Donatello and even a Léon Bakst costume design; cleverly, the saint's bee-keeping associations translate into the honeycomb-shaped leading worked into the design of her tunic. The man wore himself out pursuing new ways to repeat the same, traditional themes, startlingly striking little compositional tricks he sometimes called, jokingly, his latest "gadgett." One may take or leave the work itself, but his methodology offers potential for a whole gallery of varying artistic directions all under the larger liturgical umbrella.

I shall let the work speak for itself. Most of his designs were for Ireland's churches and homes, and remain there, though there is a rather fine if late series of chancel windows depicting angels holding the instruments of the Mass, in, of all places, Bayonne, New Jersey. More of his stained-glass can be seen up at Flickr, and Nicola Gordon Bowe (a scholar described by one art historian as a "raven-haired damsel," as if she herself were a Clarke creation!) has a very fine book out on the man, called The Life and Work of Harry Clarke, published by Irish Academic Press in 1989 and still available if one hunts around a bit.

(This post originally appeared on the New Liturgical Movement on May 25, 2009).

Friday, June 26

From the Archives: Festive Melodies of the Mechanical Organs

Daniel Mitsui posts about one of the weirder--but really, very plausible--theories out there explaining some of the discrepancies within the monumental polytyptich of Jan and Hubert van Eyck, The Adoration of the Mystic Lamb. It's been a while since I've done art history in a classroom, but if memory serves correctly, the various theories are that

a) the altarpiece was variously designed to fit in a much more monumental Gothic frame crowned with a filigree of spires a la Veit Stoss, which would mean much of the original context which would explain the apparent perspectival oddities in the composition as it stands today, considering panels have since been re-framed and perhaps moved around a bit. One version of this theory has Hubert doing the sculpting work, and reads pictor or "painter," on the frame as fictor, which works out roughly to be "sculptor." Gothic p's and f's tend to be easily confused. Even if you don't buy this particular bit of evidence, the idea that there's some missing crocketry that might have topped the panels is not so hard to believe given most medieval altarpieces were often extravagantly mixed in their media; the inmost layer of Grünewald's famous Isenheim Altarpiece is almost wholly carved woodwork. Also, a similar composition in the Prado clearly dependent on the van Eyck altarpiece includes a superstructure within the painting not unlike that which might have graced the painting in three-dimensional form.

b) Hubert van Eyck's always been a bit of a cypher in the art world--his tomb's empty, for instance, I think--and there's considerable debate as to who he was and what bits of the great altarpiece he did, despite the dedicatory inscription on the frame hailing him as even more great in skill than his famous brother Jan. In this version of the story, Jan's brother up and died on him and Jan cobbled the thing together out of some organ cases and other bits of work lying around the studio. This would explain some of the apparent iconographic discrepancies--such as depicting God the Father in the deesis where Christ would normally be; however, whether these discrepancies are that unusual for the period, or even exist in reality, is an open question.

c) A variation of the first theory, but which also includes a whole wealth of other bells and whistles, including clockwork devices to turn the panels round, and even a mechanical organ which played when the altarpiece opened. I was initially very skeptical to this wonderfully wild idea, until I remembered that this was the sort of sacred wackiness which the medievals rightly loved. Why shouldn't it be beautiful? It's only our refusal to really let go and enjoy this 'special effect' that taints it with a suggestion of the tawdry music box. I will allow myself to put a digressive plug here to once again highlight the similarities between my beloved baroque and the medieval epoch here in that I will remind you that it is the baroque that often condemned for its apparent theatricality and its symbiotic relationships with stage-sets, but it was the merry medievals that really did the most to mix theater and liturgy together (after all, modern theater grew out of medieval liturgy), often with results that would astonish and perhaps even scandalize people on both sides of the liturgico-political spectrum. I, however, simply lean back and smile to think of most of them; I am unsure if they'd strike the right note today, but perhaps in a better world, we would greet them with the right wonder and charm.

A clockwork organ and rotating panels, by medieval standards, is pretty mild stuff, actually, though it'd explain the bafflingly breathless reports that often accompanied descriptions of this whiz-bang contraption, a Jules Vernean wonder of the sort we only associate with retrofitted clockwork-driven Victorian sci-fi novels. The medievals were actually very good at that sort of thing, and it exemplifies the earthy, everything-but-the-kitchen-sink approach they took to life. When it comes to liturgical art and liturgy itself, the medievals knew how to have sacred fun, even to the point of skating dangerously close to liturgical abuse at times. Indeed, it is this celebratory liveliness and sense of interlaced symbol and practicality that appeals to me so much in both the worlds of the baroque and those of the Middle Ages. The descendent of the astronomical clock with its rows of dancing dolls is the symbolically dense and unabashedly baroque title page of an Athanasius Kircher book.

Hard scientific development and practical knowhow accompanied both the baroque--in the form of Kircher's gagetry and Galileo's science--and also that of the Middle Ages, whether it was the dull but indispensible staples such as the padded horse-collar, the mill-wheel, or eye-glasses, or the wondrously superfluous in the shape of complex astronomical clocks and other automata. (Indeed, I wonder if some will someday see the Renaissance as an essentially scientifically dead period between the medieval era and the Scientific Revolution--which may have ultimately had its pay-off in the chilly north, but had some very important roots in Jesuitical Rome). Bacon and Albertus Magnus are legendarily credited with building speaking robots of some sort (not impossible with a properly rigged-up keyboard and a bellows), and there are much more real reports of jangling contraptions designed to lower artificial angels into the sanctuary at the elevation of the Host, not to mention a set of clockwork statues of a monarch and his queen (it may have been Isabella the Catholic and Ferdinand) that once stood over their tombs that were designed to stand and kneel in time to the various movements of whatever mass was going on at the high altar of the church.

Distracting? Perhaps. Frivolous? Maybe. But certainly worthy of our wonder in an age oddly starved of it in the name of a sterile and inauthentic authenticity of expression.

Martin Travers

The altar of the Weston Chapel by Martin Travers, now in the porch of St. Matthew, Westminster.

Communion Rails by Martin Travers in St Swithun, Compton Beauchamp.

Swanwick, St Andrew. Enthroned Christ by Martin Travers, 1922.

Detail of the above.

Wednesday, June 24

Why, Exactly, are the Cistercians Keeping Silent?

Meanwhile, our friendly Wisconsin Cistercian, Brother Stephen feels left out of the Catholic conspiracy theory fun, and asks why the heck his fellow Cistercians have been spared the Dan Brown treatment. Templars? We founded the Templars! Opus Dei? We're hundreds of years older! Albino monks? We virtually are albino monks! Okay, white habits, close enough, we do get out in the sun a fair amount when working. (Leonard Nimoy voice on) Coincidence? I think not. (/Nimoy off) Not to mention all the subversive references to the sacred feminine you could slip into one of those famous Cistercian churches. Er...maybe not. Those things are pretty austere, and pink tank-tops with 'goddess' in rhinestones would kind of stand out.

But that still leaves us with the ultimate question: why, exactly, are they so darn quiet? Do they have something to hide? (DRAMATIC CHORD).

Well, probably not. But I'm sure they appreciate it if we pretend they do.

Of course, this also makes us wonder, what deep, dark plots would each of our great religious orders and societies be best suited to? (DIABOLICAL LAUGHTER). Some ideas. Feel free to chime in:

Dominicans: A massive world-wide conspiracy to calmly and rationally use careful debate to persuade the unbeliever to convert, possibly out of the hope these priests will stop talking so much. And if not, well, nobody expects the Spanish Inquisition.

Franciscans: Under normal conditions, three Franciscans could not organize a mop closet without forming five separate orders with separate charisms for tending dustrags, soap buckets, squee gees, Pledge, and Fantastik, but I suspect their decentralized organization must be some sort of brilliantly-conceived system of compartmentalized cells. Clearly the concrete St. Francises you see in so many yards really hold spy cams linked to a giant subterranean crypt below the basilica in Assisi.

Jesuits: Obviously, the core of the true secret Jesuit conspiracy is, at its heart, a vast, concerted effort to spread rumors of a secret Jesuit conspiracy. Either that, or it has something to do with cornering the market on plaid shirts.

Opus Dei: This is really just a front organization, designed to look ominous and conspiratorial (Look! A giant headquarters building in downtown Manhattan! How secretive and mysterious!) while the real power in the secret one-world government run from a bunker in rural Iowa is exercised by those nuns who wear rose-colored habits. Just listen to some Pink Floyd albums in reverse, and you'll find all the proof you need.

The Sisters of Life: Obviously, the new ninjas of the Church. They're young, fit, can rollerblade silently and swiftly, and I bet you could fit a sawed-off shotgun under one of those habits. Death on wheels.

Poor Clares: They are secretly the majority shareholders for Hulu.com.

Pontifical Commission Ecclesia Dei: Has anyone, for sure, really ever seen Bishop Rifan and Alan Greenspan in the same room? It is time to end the charade.

Carthusians: It's funny. Nobody ever comes out of there.

Anglican Use Parishes: Under the Church of Our Lady of the Atonement is a secret vault stuffed with documents proving Cranmer was really Shakespeare, Shakespeare was really Bacon, Bacon was really Queen Elizabeth I, and Miguel de Cervantes was two Iranian women and a midget under a large trenchcoat.

Redemptorists: When cornered, they subdue their enemies using their rosaries as throwing bolas.

Carmelites: Something involving Elijah, fiery chariots, and UFOs. Fill in the blanks, it almost writes itself.

FSSP: They know where Elvis, Salman Rushdie and Andy Kauffman are currently living.

Anyone I missed?

Monday, June 22

Milwaukee Mediterranean

The stylistic micro-climate of Milwaukee Mediterranean crops up all over the place in town; already unexpected, it crops up in even stranger ways than you might suppose. I have seen everything from dilapidated store fronts to half-a-dozen apartment blocks done up in its distinctive brown brick and faintly Plateresque-Romanesque detailing. First, a house or small block of flats I spotted in West Allis.

Then, a somewhat run-down commercial structure in the same style with a surprising little cupola crowning the ensemble.

And now, a Buddhist temple in a most unexpected style.

Seriously, just when you think you've run out of things to discover...

Wednesday, June 17

St. Joseph's, Wilmette

Another stop on the "Unjustly-Obscure Twentieth Century Churches of Northern Chicago" Tour was St. Joseph in Wilmette. The interior is stunning, with some remarkable marble work around the altar (and is surprisingly purple-blue with its stained glass) but unfortunately most of the photos proved too dark to be really useful. The exterior, though, is a powerfully-massed example of the Deco-influenced late Gothic revival, with an economical though carefully-thought-out application of detail.

Tuesday, June 16

Continuing the "Ecclesiastical Biography Made Easy" Theme

St. Patrick: Snakes on a plain.

St. Benedict Joseph Labre: The Forrest Gump of 18th Century Rome.

St. John Climacus: Stairway to heaven.

Armand Jean le Bouthillier de Rancé: Ask me about my vow of silence.*

Fulton Sheen: As seen on TV!

St. Lucy: No, those aren't the novelty googly-eye glasses from the Geico commercial.

*(This was actually stolen from a slogan on a tee-shirt purportedly worn by the abbot of a local Cistercian monastery here in the Midwest, according to one news article. Really. )

Caption Contest

"I really should know better zan to initiate zese staring contests with Our Lord. I zink He is going to win again."

Monday, June 15

SS. Faith, Hope and Charity, Winnetka, Illinois

I was down in Winnetka north of Chicago some weeks ago, and had a chance to visit the intriguing church of SS. Faith, Hope and Charity, completed in 1962 by architect Edward J. Schulte of Cincinnati. It is a fascinating representation of one strain of Catholic art on the eve of the Council, essentially conservative and traditional in its basic outline, if abstracted and modernistic in many of its details. In a number of respects, the result is somewhat of a period piece, but other aspects of it offer a number of ideas worthy of further exploration and development. Most of all, I appreciate its bold colors, rich gilding, and use of noble materials within this hybrid context.

(Yes, rubber doormats and Latin. It was an interesting time! Nice to see they're still there.)

Tuesday, June 9

A Baptist Walks Into an Orthodox Church

[...] Long, complex readings and chants that went on and on and on. And every one of them packed full of complex, theological ideas. It was like they were ripping raw chunks of theology out of ancient creeds and throwing them by the handfuls into the congregation. [Theological feeding frenzy! I love it! --MGA] And just to make sure it wasn't too easy for us, everything was read in a monotone voice and at the speed of an auctioneer.God bless this man, he gets it! More here.

I heard words and phrases I had not heard since seminary. Theotokos, begotten not made, Cherubim and Seraphim borne on their pinions, supplications and oblations. It was an ADD kids nightmare. Robes, scary art, smoking incense, secret doors in the Iconostas popping open and little robed boys coming out with golden candlesticks, chants and singing from a small choir that rolled across the curved ceiling and emerged from the other side of the room where no one was singing. The acoustics were wild. No matter who was speaking, the sound came out of everywhere. There was so much going on I couldn't keep up with all the things I couldn't pay attention to.

[...]

So what did I think about my experience at Saint Anthony the Great Orthodox Church? I LOVED IT. Loved it loved it loved it loved it loved it. In a day when user-friendly is the byword of everything from churches to software, here was worship that asked something of me. No, DEMANDED something of me.

A Curiosity

Government Street United Methodist Church--intriguing not only as a Methodist church in a revived Spanish Baroque style, but as a Spanish Baroque church in Mobile, Alabama, and a reasonably well-done one at that. (Though as Cram and Goodhue did a Spanish Baroque Methodist church in Massachusetts (!) anything is possible.) The building was designed by George B. Rogers and built 1889-90. More photos here.

Tuesday, June 2

Dancing in the Streets

Incidentally, freshman year of my time there, the one Latin mass held on Notre Dame's campus, sponsored by the now-defunct Medieval Society, a.k.a. the Worshipful Company of Our Lady of the Lake, was done, for reasons that remain obscure to me, on St. Willibrord's day in November, with the proper medieval chants and a sequence for his feast. This custom appears to have died out, but fortunately the Latin Mass can be found once or twice weekly on campus now, sometimes in the Novus Ordo and more frequently in the Extraordinary Form.

Things That Puzzle Me

A YouTube music-video consisting of photos of Benedict XVI set to a recording of I Will Survive. (Okay, yes, I get it...but how the two ideas got together in the first place is the real mystery.)

The Wikipedia page titled "List of Unusual Deaths."

And Uncle Fester is John XXIII

Monday, June 1

Do-It-Yourself Home Reparatory Kit

That being said, it suddenly brought to mind all the other reparatory activities that might not work out quite so successfully:

Reparatory water-balloon fights

Reparatory Beaujolais Nouveau wine-tastings

Reparatory stand-up comedy (unless it's listening to Carrot Top and offering up the accompanying pain)

Reparatory napping (a ministry of the Canons Regular of Our Lady of the Dormition)

Reparatory square-dancing

Reparatory fight club

Reparatory home repair

Reparatory badger spoon-poking

Reparatory accordion serenades (accordions being intrinsically evil)

Reparatory mime and street performance

Reparatory celebrity bowling tournaments

Reparatory charades (I'm told Trappists do this regularly)

Reparatory snacking (Hot Pockets also being close to intrinsically evil)

Reparatory extreme sports (though as the Olympics started out as a pagan religious festival, the idea could be baptized, one supposes)

Reparatory ultimate frisbee

Reparatory crowd-surfing and mosh pits

Reparatory World Wrestling Federation

Any others?