Sunday, June 28

Harry Clarke, Ireland's Master of Stained Glass

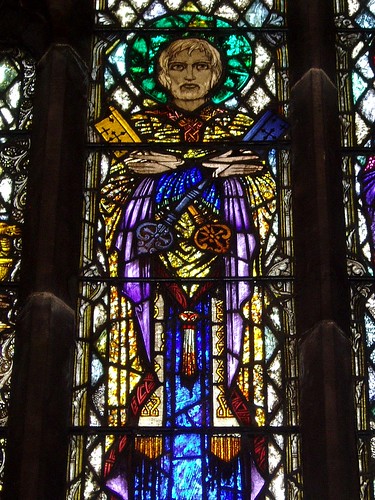

Due to an offhand reference by Fr. Symondson, the noted Jesuit who needs no introduction here, I discovered some time back the incredible oevre of the Irish stained glass designer and illustrator Harry Clarke. Curiously enough, I had already stumbled onto one of his best works on a previous trip to Ireland, a suite of stained-glass windows for a convent chapel in Dingle, and promptly forgotten about them. (The docent claimed Clarke could not draft an ear properly, so he covered them with drooping sidelocks, something manifestly untrue when his other work is studied in detail.)

Clarke was a brilliant, tragically shortlived fin de siècle workaholic whose designs are often simultaneously extremely iconographic and also bold, strikingly original and even mildly unsettling at times. (His illustrations for Poe's Tales of Mystery and Imagination are still, unsurprisingly, in print.) Nonetheless, he is one of the few artists of the past hundred years who managed to take the best out of the art of his contemporaries and bring it, somewhat purified, into a well-thought-out and elegantly-designed liturgical context that is exceptionally rich with symbolism at all levels of his design. (Who else could slip a reference to Klimt into an image of St. Brendan, and still make it work?) The iconography is, mostly, quite traditional, but often approached from unusual and affective angles: his stunning redheaded St. Gobnait, is quite conventionally liturgical, but draws on the work of Donatello and even a Léon Bakst costume design; cleverly, the saint's bee-keeping associations translate into the honeycomb-shaped leading worked into the design of her tunic. The man wore himself out pursuing new ways to repeat the same, traditional themes, startlingly striking little compositional tricks he sometimes called, jokingly, his latest "gadgett." One may take or leave the work itself, but his methodology offers potential for a whole gallery of varying artistic directions all under the larger liturgical umbrella.

I shall let the work speak for itself. Most of his designs were for Ireland's churches and homes, and remain there, though there is a rather fine if late series of chancel windows depicting angels holding the instruments of the Mass, in, of all places, Bayonne, New Jersey. More of his stained-glass can be seen up at Flickr, and Nicola Gordon Bowe (a scholar described by one art historian as a "raven-haired damsel," as if she herself were a Clarke creation!) has a very fine book out on the man, called The Life and Work of Harry Clarke, published by Irish Academic Press in 1989 and still available if one hunts around a bit.

(This post originally appeared on the New Liturgical Movement on May 25, 2009).