Monday, September 29

I've been waiting for this for a long time. The Return of the King trailer is online. You know a movie is going to be good when the even the trailer gives you goosebumps.

The Winged Beasts of the Nazgul look to be much scarier in this movie, I'm happy to say. I'll never forget the first time I read about the Black Riders as a child:

"A sudden dread fell on the Company. 'Elbereth Gilthoniel!' sighed Legolas as he looked up. Even as he did so, a dark shape, like a cloud and yet not a cloud, for it moved far more swiftly, came out of the blackness in the South, and sped towards the Company, blotting out all light as it approached. Soon it appeared as a great winged creature, blacker than the pits in the night. Fierce voices rose up to greet it from across the water. Frodo felt a sudden chill running through him and clutching at his heart; there was a deadly cold ..."

I hardly slept at all that night, as I recall. If the moviemakers manage to capture even one-tenth of what Tolkien had in mind on this last movie, it will be well worth seeing, to say the very least.

Thursday, September 25

St. Francis and the miracle of the first Christmas creche.

Giotto, Upper Basilica, Assisi. (Image Credit: Storia dell'Arte).

I'll Say Hi to il Poverello For You

Well, I'm off tomorrow (leaving at some unholy hour of the morning, especially by Italian standards) on a field trip with my class to the quaint cities of Umbria and Tuscany for a week. I will not be back until October 6, and trust me, by then I will have reams of notes and adventures to pass on. Knowing my mile-a-minute professors, hitting internet cafes will not be an option. And perhaps the break will do me good.

We'll hit Orvieto, Assisi, Gubbio, Urbino, Lucca, Siena and finally Florence, the city that gave to the world a weirdly schizoid array of saints, sinners and none of the above. Names like Fra Angelico, Savonarola, Michelangelo, and Nicky Machiavelli spring to mind. I'll be covering territory both new and old to me.

Assisi will be beautiful, a city where I will finally experience the sights and sounds of the real St. Francis rather than that crumbly concrete garden-gnome avatar we're so used to. Florence will be like visiting an old friend again, and I can finally get over to the Boboli Gardens and see what I've been missing all this time in the way of grottos and charming Medici self-glorification. I'll watch out for wolves in Gubbio, of course. Perhaps I'll even catch a glimpse of the Volto Santo (sometimes thought to be the Holy Grail) at Lucca. It's a long hall, but I shall, to continue the MacArthur theme, return. A doppo. Ciao ciao.

Well, so we were trudging through the Forum, and the day was turning from pleasantly pastoral to just plain hot, when I spotted another potential entry for A Field Guide to European Nuns, a suppliment to the magnum opus prospectively entitled James Audubon's Nuns of North America that Emily and I are planning to compile some day when we have ludicrous amounts of free time.

Anyway, as habits go, this has got to be one of the more unusual ones. First, let me explain she was in a big herd of priests and religious, including what might have been a Cistercian or a Dominican laybrother in black scapular, white tunic and broad black fascia. Without that context I might have mistaken the young woman for an Anglican cleric or maybe even a Lutheran minister. She was a tall, well-balanced, amazonian sort of woman, hatless, with bobbed hair of an almost geometric rigor. She was wearing what can be only described as a female cassock. It was buttonless, cream-colored, pleated down the front in a manner that resembled a scapular, with a high standing collar and narrower pleats down the back. She wore a narrow sash at her waist, ties hanging to her left, resembling in cut the cincture worn with a Jesuit-style habit. Unremarkable shoes, big satchel slung over her shoulder, a gold Greek cross with lobed ends hanging at her chest. Like me, she looked tired. And then she disappeared into the touring group, trudging off towards the Arch of Septimus Severis. Just another pilgrim out of millions.

Quite peculiar. I usually can recognize these folks, but this time I'm stumped. Almost. The author of the (surprisingly funny and almost reverent) book When in Rome: A Unauthorized Guide to the Vatican noted he saw a similarly-dressed woman in St. Peter's Square once, except she was in sky blue. He also describes her, strangely enough, as wearing a Roman collar, probably a misinterpretation of the plain high collar of young nun I spotted. He asked her what organization she represented and she said it was an Italian order, the Oblates of Our Lady of Fatima. Also unknown to me. I can't find a scrap of information about this group online, too, which deepens the mystery. Most interesting. Perhaps one of my learned and gentle readers can shed some light on this sartorial-monastic curiosity?

Image credit: BramArt

"Behold, I Make All Things New"

How can we contrive to be at once astonished at the world and yet at home in it?

--G.K. Chesterton

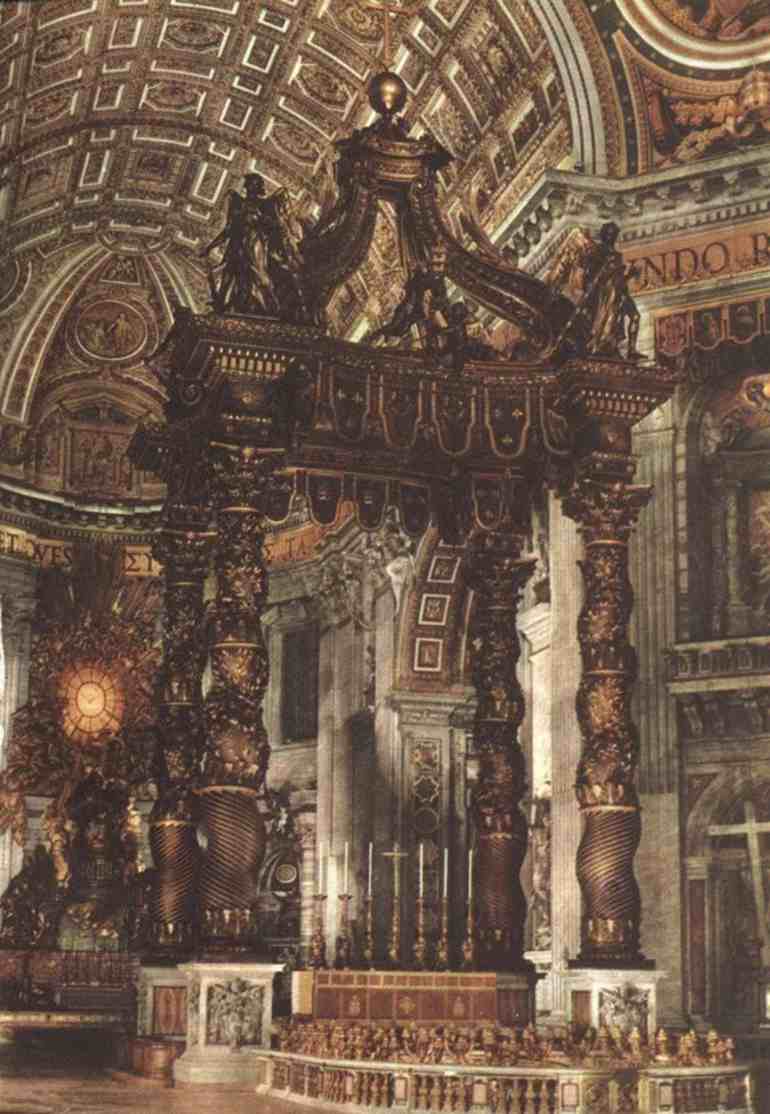

Yesterday evening, I visited St. Peter's with a Protestant friend of mine attending the architecture program. We were looking (it turned out in the wrong place) for the Daughters of St. Paul bookshop and ended up visiting the Libreria Ancona on Piazza Pio XII to pick up a pocket Catechism and a New Testament for a theology class. Since we were probably a scant hundred yards or so from this umbilicus mundi of Catholicism, and my friend had never visited the Vatican, I persuaded her and some of those accompanying us to go in and see St. Peter's.

Catholics, as I have said before, are all-too-familiar with the Basilica. Our images of it are set by the time we gain the age of reason by tiresome repetitions of it in textbook, art books, and television. To my Protestant friend, equally unaware of Catholicism and its detractors, our visit came as a glorious surprise. It proved infectious.

St. Peter's is a realm of delightful unexpectedness. It isn't just novelty, but the sheer size and weight of this universal, cosmopolitan, cosmic institution envelops you like the whirling baroque shroud of blazing pophyry inlay that drapes the tomb of one of the Chigi popes. Luck, or perhaps Providence, was on our side, as we reached the Arch of the Bells as the clocks struck six and the Swiss guards on duty changed the watch with the Germanic bark of orders and the clank of halberds and partizans. We lingered in the narthex for some time, my friend overwhealmed by the beauty of it all. Even the seemingly-simple but ornate coffers on the ceiling which I had mentally brushed aside, too familiar with the baroque and too familiar with St. Peter's, fascinated her.

We moved through the aisles the vast marbled basilica for almost an hour, my commentary occasionally broken by her own reactions of mingled familiarity and surprise. Even to me, my mind steeped in florid tales of incorrupt saints and levitating friars, her excitement made this familiar place seem exotic and blissfully foreign. I remembered to look around as well as lecture. She was full of questions, wondering why we kissed St. Peter's foot or the significance of the baldachino or why Blessed Pope John was miraculously preserved in his glass sarcophagus. It was a place of the senses, filled with light and colors and the omnipresent odor of incense, a much heavier, more solid religion than we often encounter back in the United States. It was marvelous.

We could hear chanted prayers coming from the apse under the billowing gilt of the Throne of Peter, and found ourselves amid a vast crowd of pilgrims hearing the end of Mass from the altar there. Six candles burned in the choir, while ranks of priests in white surrounded the foreign bishop presiding from a cathedra and folding lectern far beyond.

The organ sounded, and a procession wound its way from the altar, acolytes in black and white followed by knights and ladies of the Holy Sepulchre with scarlet crosses marked on their shoulders. Then dozens of deacons and priests, and finally a bishop all in gold flanked by his two dalmaticked assistants, huge tassels swinging at their backs. Behind them loomed a huge sedia borne up by eight priests in chausibles beating a smoke-darkened statue of the Virgin swathed in purple velvet, crowned and studded with stars. It was something out of a novel, a baroque painting, both primitive and incomparably complex, the Virgin's face as dark and chthonic as an antique sibyl's, the priests clothed in white out of the Book of Revelation. It was strange and unfamiliar; but it was always what I had dreamed about. I had come home and discovered a new continent in the process.

Perhaps my friend thought it was pagan, supersititious, bizarre. But her face never told me that. If she thought it was heathen, she clearly thought it was strange and glorious as well. And I am glad that I was there; not to preach or praise, but simply to drink the vast sacramental banquet in with my eyes.

Wednesday, September 24

Today, Zenit announced the release of software to assist couples with using NFP. Someone should have told them that Envoy came up with this last year. (Scroll to the bottom of the page to see it)

Our Lady of Walsingham (Image credit: W.F.F.)

Today is the feast of the famous shrine of Our Lady of Walsingham, known sometimes as the Virgin by the Sea, founded in 1061 after the aristocratic Lady Richeldis de Faverches had a vision instructing her to build a replica of the Holy House of Nazareth. This predates the shrine at Loreto, which only appeared in Italy during the following century. An Augustinian canonry grew up around the oratory, and soon it became a thriving center of English devotion. However, in 1534, the monks sold out, signed the Oath of Supremacy of Henry VIII, and watched over the dismantling of their monastic treasures. Dissenters were executed, and in 1538, the statue of Our Lady was burned in London. The shrine soon became little more than a cattle barn.

Pope Leo XIII, amid the growth of English Catholicism at the turn of the last century, re-founded the shrine in 1897, and a new statue was erected in 1922, marking great cooperation between Catholics and Anglicans. The shrine still represents this, and both English Catholics, high-church Anglicans and Anglo-Catholics hold a great reverence for Our Lady under this title. The feast was re-established in 2000 on this date, and in Texas, a church of the Roman Catholic Anglican Use was erected under her protection in June of 2003.

Today's a big day for Our Lady generally-speaking. She's also honored on this date as Our Lady of Mercy or of Ransom today, which commemorates her miraculous part in the founding of the Mercedarian Order in Spain, who would pay the costs of freeing Christian captives from the Moors.

Today is also the feast of Bl. Anton Martin Slomsek, the Slovene Prince-Bishop of Lavant in the Austro-Hungarian Empire; as well as St. Gerard (or Collert) Sagredo, a martyred friend of St. Stephen of Hungary; St. Pacificus of San Severeno, an ecstatic philosophy professor; and St. Geremer, an ex-Merovingian courtier who founded the abbey of Flay and who was nearly murdered by his monks for being so strict.

Tuesday, September 23

Ceiling of Sant' Ignazio (Image from Distance Learning.)

Amazing Grace at Sant' Ignazio

The concert proved to be a most excellent experience. Sant' Ignazio looks stunning at night, torcheres and candelabra shining off glass-smooth expanses of scarlet-veined marble and Corinthian volutes. The Coro Cinese di Long Island (to quote the program; the genial MC pronounced it Longa-Ieesssland, by the way) performed three spectacular motets by Pittoni, Palestrina, and Bruckner; two modern Alleluias. Then there came, sung by a young soloist with frosted hair, a truly bizarre but well-executed Evening Hymn by Purcell that sounded closer to a Balinese transcription of Hildegard of Bingen than anything English. Maybe someone pulled a fast one on them with the sheet music; nonetheless, whatever it was, it was wonderful. Besides that, there was, perhps slightly incongruously, Leonard Bernstein's A Simple Song with organ accompaniment, plus two Rutter works. Lastly, as Fr. Jim predicted below, came not merely one but four vigorous American spirituals.

As the choir moved towards the conclusion of its performance, I stole away to one side and lit a candle to St. Aloysius. I watched the snuffed-out smoke of the taper I had used to transfer the flame undulate in the candlelight. It sent up gauzy tentacles into the darkness, catching the heated updrafts of candle flame like a smoky jellyfish riding the currents, and as I watched them, I heard the glowing, etherial Rutter setting of Amazing Grace, harmonizing oddly well with the gilded angels and lapis of the ornate altar before me.

Nota Bene: For visitors from Dappled Things coming to the Shrine looking for my posts on Viterbo and Bagnaregio, scroll down to Monday's posts. Prego!

Deeply Suspicious. (Image credit: Dartmouth College.)

How to Recognize a Freemason

I think my search for crank-free Tridentine parishes here in Rome has finally succeeded. The two masses I have been to at San Gregorio and at Gesù e Maria have been quietly beautiful, reverent and, most importantly, free of weird politico-ecclesiastical posturing by either the celebrant or his parishioners. Plus, I'm not the only person there in a tie.

This is not to say my search hasn't had a few setbacks.

For example, I went to a Requiem mass on Saturday morning and instead ended up striking a blow against the dark and nefarious embrace of International Freemasonry. Which entailed sweating in the sun under the Porta Pia monument for near over an hour while unemployed geriatric Roman aristocrats shouted indecypherable Italian slogans at me through megaphones.

Yes, this is going to take some explaining. Not just to you, but mostly to me. I still have no clue what the heck just went by me.

I didn't plan it this way. It all began with the Tridentine Requiem I heard at the church of Corpus Domini on the Via Nomentana this morning. It was amazing. There was a palpable visual shock as he entered from the sacristy, flanked by his attendants, all in stark black and white. The priest, the Uruguayan Fr. I., was dressed in the silver-trimmed mourning vestments of the old rite, while his servers wore sober cassock and surplice. Even his usual quick Latin prayers were slowed by the solemnity and sadness of the occasion, resonating in the eerie echo of the neo-Gothic sanctuary as a chant schola intoned the age-old Dies Irae. Sublime.

The mass was said for the repose of the souls of the Papal troops and their adversaries slain at the battle of Porta Pia in 1870, when Garibaldi's soldiers stormed the Eternal City and left Pius IX a self-proclaimed prisoner in the Vatican. This strange echo of the past gave the whole Requiem a weird poignancy, tragic and sad. Soon, however, the sublime became ridiculous.

Like everything in Italy, tragedy is not so far from comedy. So, things started getting weird in short order. The homily seemed encouragingly non-political enough, something something culture of Death, something something Giovanni Paolo, something something Ratzinger. Fr. I. told me afterwards it was about the European Union, which means I have to practice my Italian. That being said, while I'm no big fan of the E.U., it seems slightly odd as a sermon topic at the memorial of slain heroes.

It gets better.

There was going to be a wreath-laying ceremony at the Porta Pia monument afterwards , and while hesitant, the tourist in me I decided to tag along. Then the fun began. The first sign of weirdness ahead was the tubby gentleman at the head of the procession with the St. Michael tee shirt waving a gonfalon with the words Vive le Christ-Roi, Roi de Canada, hardly strange but highly incongruous in the midday heat.

I wasn't sure it was any of my business, knowing the sort of monarchist craziness that occasionally rears its hoary head in traditionalist circles, and stayed on the periphery of the crowd with an elderly English-speaking woman I recognized from my visit to that parish in Trastevere. I figured if I ran into any loopiness at the least it might have comic-relief potential. Surprise, surprise.

The twenty or so people who had formed the congregation made their way towards the column and soon became a tourist attraction for some highly amused carabineri on duty near the cenotaph. Fr. I. blessed the wreath with a screwtop aspergillum, and turned the floor and the megaphone over to a cadaverous gentleman in a bad suit.

I later found out he was Prince Ruspoli, though I'm not sure why that means anything. Perhaps if he was a Farnese or Spada, I'd think different, but his name sounds more like a flavor of ice-cream than a papal nobleman. He wound up his mumbled speech on the battle of Porta Pia with the faintly anachronistic slogan "Vivan i stati pontifici, viva il Papa-Re." Huh. "Long live the Pope-King." I realized right now I was on a rather different planet than I expected. Not a bad thing, but just...well..weird, given all these resentments between Italy and the Holy See got sewn up decades ago at the Lateran Accords.

The slogan got a few lapsidaisical cheers from the small crowd. I wondered if I could sneak out without the old lady noticing, but, while being on the edge of the crowd, it was still a small crowd and I didn’t want to be rude. It was getting hot and I was losing interest.

Then the Prince's brother, who seemed to have inherited the snappy-dresser genes, took over the bullhorn and proceeded to go at it for at least forty-five minutes. I soon realized this was too crazy to miss, given the puzzled, incompetently stoic, or incredibly bored looks he was getting from his audience. Even Fr. I., who had been standing for two hours straight between the Requiem and this miniscule funeral rite-turned-rally, winced a little and seemed to be having trouble keeping his eyes open.

I wish I could tell you what he was talking about, but it looked like there wasn't anything he didn’t talk about. Well, th central theme was obvious, though. Those pesky Masons, you know, scourge of Europe. Who, between you, me and the wall, frankly haven't packed a punch since the French Revolution, but don't tell him that. The word Masoneria popped up about once every three sentences, and there were, as far as I could tell, paranoid rantings against one-world government, the European Union, something about the pure monastic democracy of Mount Athos, Italo-American gibberish like gangsterismo and possibly Jacques Chirac. Maybe Masons in the European Union are threatening to take over Mount Athos using Luigi "the Shoulder" Vanvitelli and turn it into a vacation home for French mimes. I got the impression everyone else around me was just as confused.

The deceased Papal troops themselves had vanished in this conspiratorial mess.

I'll get into this more below, but, while as a Catholic I have my theological difficulties with the rich old guys in rolled-up trousers who have persecuted the Church in the past, I rather doubt they're out to kidnap me and force me to watch My Mother the Car as part of some nefarious plot to destroy the Vatican. There's already one of those plots, and it's called Popular Culture, and it's bad enough without dragging in a secret society out of a detective novel.

Eventually, the still-dazed Fr. I said another prayer (through the bullhorn), flipped his stole around so the white bit faced outward, and solemnly blessed us, at which we all knelt. And thus it ended, a whole half hour behind schedule.

The old woman gave me the gist of the speech over a sausage panino at a cafe across the street. It only further confused things, really. She told me what I knew already, Garibaldi's seizure of the Papal States, the death of the Papal soldiers, and so on. But she also said that today was a big holiday for the Pope's adversaries, whoever they were, which she didn't elaborate. She explained some sketchy ideas of Not-the-Prince's about low interest rates which were completely lost on me. When we popped outside, she finally gave me the name of these unknown enemies.

She was talking about…(dramatic chord)…the Masons. Well, of course, given that speech I heard. Strange to get all secretive about it with Not-the-Prince shouting it from the rooftops.

I had to see what would come out of her mouth next so I continued around the block with her, wondering bemusedly if the window cleaners were listening in on us. She'd already been concerned the bartender had been listening in. I would be too, but only because this was all hilariously embarassing. Of course, the street was full of plenty of potential Lodge spies cunning disguised as pedestrians, but that didn’t seem to enter into the poor woman’s head. If the Papa-Re thing had left me somewhat confused, I was now in the Bizarro universe.

I made a mental note to avoid Fr. I’s parish because, well, I live in the real world and not in a particularly convoluted episode of the X-Files. Most of the time, at least.

It got yet stranger. The folks intent on taking over the world, the folks behind all this, the old woman explained, were not pure Masons, of course, but they're in league with Communists, the guys who put eyes and pyramids on dollar bills, and some of your typical conspiratorial financiers (gangsterismo?). Uh huh. Whatever you say, ma'am. Being somone who's read Umberto Eco's satirical conspiracy-theory novel, Foucault’s Pendulum, at least twice, I knew the script. The late Madame Blavatsky showed up in the next few minutes like clockwork as one of the conspirators, as did the incompetent, petty but hardly scary European Union, the Founding Fathers, one-world government, and what was probably that strange little French village Rennes-le-Chateau. I could just see the Holy Grail heaving into sight on the horizon. Jeez.

That's my cue to leave, I thought. I thanked this most peculiar woman for her insight, and decided to excuse myself before the Knights Templar (incognito as Trilateral Commissioners) showed up in a black helicopted piloted by Elvis and Salman Rushdie.

It's comical, in a weird sort of way, but also sad and pitiable. The Tridentine mass has a place in the Church as worship, not as a vehicle for political paranoia. Masonry was a threat to the Church once, but right now a bunch of old men in funny aprons are the least of our worries. Maybe it’s different in Italy. The notorious P-2 Masonic Lodge scandal happened only about two decades ago. And then, walking back, I saw an enormous anticlerical poster on the city gate proclaiming NO VATICAN, NO TALIBAN which made my blood run cold. Dear God. The work of the Masons? No--not now. I can't joke about something like that.

Whatever the case, the Church’s problems won't be solved by blaming them on once-powerful, now illustory cabals.

I had a troubling if quiet walk back past Santa Maria della Vittoria, which was, of course, closed. Nobody followed or anything, though I imagine the Masons you don't see are the problem. It was all too much to take; too completely, monumentally absurd, that people could take this sort of fear-mongering seriously. I found my way along Via XX Settembre past the Presidential Palace and finally, atop the Quirinal hill, beheld the whole city at my feet. The great bulbous dome of St. Peter’s in the blue distance came as a splendid breath of fresh air, and I laughed. It felt very good.

Padre Pio. From Catholic Forum Online.

Levitation, Tobacco, and Roses

Today is a very exciting feast, that of St. Pius of Pieceltrina, better known to his millions of votaries worldwide as the humble Capuchin stigmatist Padre Pio. He is a saint of our own era, having died only as recently as 1969, one of the most recent saints to be elevated to the glory of the altar.

He was said to be capable of being in two places at once, of healing by touch, and also was able, like fellow Franciscan St. Joseph of Cuptertino before him, to levitate. He could read consciences, heard confessions by the hour and was often an unwitting tourist attraction for the curious after his fame was spread to America by tales brought back by returning GIs after the Second World War.

He received the five wounds of Christ early in his life, in 1918, becoming the first priest to be so blessed by this mystical experience. His bilocation was particularly phenomenal, as he appeared on other continents. He was usually accompanied by a peculiar smell of roses (or possibly tobacco), which seemed to emanate from his wounds.

He was once astonished to discover that a plane flight to the U.S. took six hours while he was capable of the journey in seconds. Even weirder was his spectacular aerial appearance over the town of San Giovanni Rotondo during the Allied liberation of Italy, when he spared it from unwarranted bombing by American troups. His stigmata vanished after death, and he also never celebrated the new Mass, which he could never quite cotton to.

It's hard to top all that in terms of the sanctoral cycle, but I'll take a crack at it. Today's also the feast of St. Clare of Assisi, the Italian patroness of television, who, bedridden, once saw vision of a faraway Mass projected onto the wall of her cell. She is also patroness of eye disease, embroiderers, gilders, and television writers.

Then there's Bl. Emilie Tavernier, who had a pretty cool habit for her Sisters of Providence. There's also St. Guy of Durnes, who revised Cistercian chant at St. Bernard's request. Lastly, there's St. Linus, the second Pope, who hasn't much of a claim to fame except for his mention in the Canon sandwiched between Peter and Cletus. So much for that.

It's very hard to top Padre Pio, really; he's just too cool.

Monday, September 22

One of my favorite professors at the School of Architecture, David Thomas Mayernik, is publishing a new book on the civic legends of Renaissance Italy. Mr. Mayernik, who recently returned to full-time practice, is also an accomplished fresco artist, watercolorist, and expert on the Baroque. And he paints beautiful things for real chapels, for goodness' sake! I ask you now, what's not to like? I have not yet been able to get my hands on his new work myself, but he is an insightful theorist, an excellent architect and a good Catholic gentleman, so it's gotta be good. Read a sample from the first chapter here. And then go buy it, thankyousoverymuch.

Also, watch this space in particular as the School of Architecture will be publishing a retrospective of student work (tenatively) titled Acroterion (it's a term for a Greek temple doodad), including several projects by yours truly.

Old Viterbo: Part of the Former Papal Residence, now the Bishop's Palace

St. Rose of the Machines

I told you already that the second stop after our strange sojourn in Bagnaregio's miniscule old quarter was the bustling city of Viterbo, an industrial center wrapped around a remarkable medieval town crowded with twisty passages overhung with quaint casapontes, houses that literally bridge the street. It is a grey town, built from a uniform pepperino that makes the entire place seem carved into the rocky sides of cliffs, but it is the warmest and most sun-soaked grey town that man has ever conceived.

It's also the only place where I've seen an antique car rally roar down streets that look narrower than some people's driveways back in the States, the thundering old machines directed around a dozen hairpin turns by the city's miniscule traffic police force, all of whom seemed to be uniformed, uniformly young blonde girls in uncomfortable shoes wearing silly WAVE-style hats. It might have been in honor of the Festa di Santissimo Salvatore, posters of which were everywhere. The other part of the festival involves a parade of noblemen dressed in mediaeval garb. Cars and knights. Strange.

Something's subtly off about Viterbo, whether it's the nonchalant mixture of modern and ancient, of straight streets and crooked Gothic alleys, of history and creepy kitsch. A few doors down from the chaste pink stucco facade of a church, on a main street, is, of all things, a garishly-liy window display given over to incomprehensible leather clothing doubtlessly used by consenting spouses, a cross between Torquemada's couturier and one of Vaucanson's eighteenth-century clockwork women. I quickly moved on and tried not to think about it.

Viterbo seems to make a cult out of weird holidays that revolve around machines and the Middle Ages. There's that auto rally, but I can top that easily. The biggest date in the secular and civil calendars is September 3, the feast of Santa Rosa, the town's teenaged patroness, which is comemorated by the festive and incomprehensible custom of building enormous portable tower-shrines called macchine, a cognate of machine which is closer in meaning to a parade float or a ceremonial cart. The pictures make them look weirdly half-Hindu, enormous spindly pagodas rising fifty feet into the air and encrusted with praying angels, supported by hundreds of back-bent semi-Spanish confraternity men. I even wandered through a half-open door into an old church given over to the pageant's props, strange, dark and gloomy, while enormous prop lions loomed over me in the baroque murk. I never did find that church again. Viterbo, like I said, refuses to make sense.

Even something so weirdly straightforward as an incorrupt body isn't quite right in Viterbo. Let me explain. That magnificent young nun St. Rose has long been a favorite saint of mine, and being among her machines made me wanted to see some flesh-and-blood reminder of her memory. I was in luck as I finished sketching about half-an-hour for the bus was ready to leave and dashed across the old town to the looming neoclassical shrine dedicated to her incorrupt body.

Like I said, nothing is what it seems in Viterbo. The term incorrupt is a flexible one, something we often forget as we are conditioned by the beautiful memories of the Little Flower's recumbent form in her glass altar, half sweet milk-skinned Snow White, half swooning Bernini ecstatic. In many instances, it seems to relate to a slowing of bodily corruption, for even saints must suffer the corruption of original sin, no matter how slowly. Many incorruptibles look like St. Teresa of Lisieux and the popes entombed at St. Mary Major, but others have faired worse over the centuries. Whether by Divine design or by the result of a fire that struck the old church, disappointingly, one of them is St. Rose.

It was with an odd mixture of awe and disappointment that I beheld her wizened, brown corpse in the glass urn, draped in Franciscan grey. It was miraculous that so much of her had survived after eight hundred years, but miracles aren't always pretty. She looked more like Mother Teresa than an eighteen-year-old firebrand, and the tip of her nose had gone missing.

But, standing there, I still remembered that this was the face of a saint, for all the hardship visited on her, and tried to reconstruct it in my mind. She was small and slight and lean, with what might have been a beautiful face once. As I stood there, looking through the grillwork, I thought of her, imagining a slightly shallow, high-cheekboned face; perhaps with small, thin lips; a pert, snub nose. She seemed to be inevitably blonde and pig-tailed in the pictures. Like her corpse, in so many images she was slight and pale, and soon between the body and the image, I could imagine her as she was.

Then I realized that was wrong, too.

This imaginary reconstruction, this little pale saint, didn't look like the holy nun or precocious preacher I knew from my books. She seemed more like the quiet, quietly pretty little high-school girl who sat in the back, got good grades, and stayed behind to clap erasers after class. I could have passed her in the Notre Dame dining hall back home without a second thought. And yet, this little creature had challenged a blasphemous emperor at age 11, gotten herself and her whole family exiled for her trouble, and died in the odor of sanctity before turning twenty. It boggled the mind.

And yet I remembered Mary's cry of exaltavit humiles, of the God Who raises the humble, and I thought in this bizarre town of archaic automobiles, scary leather-clad mannequins and streets at once sunny and mysterious, that this little saint was the only thing that made an ounce of sense.

A Visit to Civita di Bagnaregio

The secretive Etruscans, whose language and culture remain an eerie puzzle to archaeologists, always divided their villages into two worlds, a city of the living and a city of the dead. In the north of Latium, the tiny medieval town of Civita is built upon such a necropolis, and it too, is slowly withering away. It has been known for centuries as "the dying city." The pockmark holes of the cave-tombs of these ancient mystagogues line the cliffs that ring the great wind-bitten outcrop on which the tiny village stands.

I visited the dying city last Friday.

Civita lies some miles outside of Viterbo, and is itself the old quarter, now isolated and abandoned, of the equally tiny city of Bagnaregio, sometimes also called Civita di Bagnaregio. The strange outcrop on which it stands rises in striated geological strata. It is now mostly a plug of hardened clay, its outer casing of porous tufa lost to the ages, scrubby yellow-green plants clinging precariously to its slopes.

As it rises, strata soon shape themselves into knife-hard edges which slowly themselves become the steep golden-brown pepperino ramparts of the town, seemingly forged from the living rock by the hand of God or perhaps some darker Etruscan deity. Some day soon the plants on its slopes will wither and the clay will start to crumble like the stone did before it.

The town is a sea of low-peaked tile roofs, the only verticals the tower of the single church and its cross-crowned pediment rising against the pale cerulean silhouettes of the mountains r ising ghostly in the distance. A handful of stubby, bizarre chimney-pots occasionally break the rhythm.

There are few who still live here, and it seems they live in another age, one where the distinctions of the centuries seem to fade. The church seems just as old as the truncated half-buried Roman columns that stand in the dirt-floored main piazza, used for the yearly donkey race, one tiny shard of a vast civic calendar now abandoned. Flower garlands had gone up in honor of this single town event on the church, a vast geometric carpet of wilting leaves and blooms blanketing the floor of the nave.

I spent some time wandering through the jagged streets, catching slitlike glances of the verdant valley hundreds of feet below me, and then came back to the church. Someone was using a vacuum cleaner, but only that broke the silence. Somewhere around here, the Seraphic Doctor and cardinal St. Bonaventure grew up, and his image adorns one of the tiled street signs of a narrow alleyway near the main piazza, little more than six feet wide. His image adorns one wall in the little church as well, a strange, inexplicable little sanctuary crowded with millenia of memories.

It seems more like some incogruous Catholic outpost of Indian Mexico or some contested shrine in the Holy Land than the parish church of a dying town in Italy. Outside, ionic volutes slowly shrivel while the cracked pepperino stands solid against the piebald, stained pink stucco crumbing in great dry gaps. Dozens of unlit oil lamps and candelabra hang from the arches of the nave. The sanctuary's high altar still faces eastward, festooned with gilding and bizarre shades of sea-foam green. Every pillar is marbled in weird, unnatural colors, purple pophyries and aquamarine, vying with the great boughs of scarlet and yellow flowers that decorate the altar.

Yellow-wax votive candles stand in great banks on the floor. The place is a riot of pious clutter, with abandoned Corpus Christi torches and a canopy propped up against bare walls studded with torchere-bearing angels, fragments of fresco, and unsettlingly baroque shrines. Two side-altars flank the sanctuary, the right serving as the tomb of the wax-encased skeleton of a bishop St. Hildebrand buried in faded pontificals. It is a weirdly taxedermic memorial, his beard looking like a disguise and a thick gold wire halo encircling his mitre.

To the left is the town's patroness, the delicate martyr Vittoria, a beautiful little creature dressed in silk with perfect classical features sharp as the prop dagger that pierces her small wooden breast beneath faded robes, rich as her sculpted gilt hair. Her bare toes peep out from the embroidered hem of her robe bound in scarlet-banded sandals. Hildebrand’s sleep seems fitful, Vittoria's strangely peaceful, the very allegory of this dying city.

It may seem secretive as the indecypherable tongue of the Etruscans who went before them, but the mystery that lies behind this town's eerie moldering serenity is not completely lost to us.

The death of a city is not always one of decadence and decay or urban decline. We forget that as inner cities collapse into graffiti and murder. But death can be holy too, something we are afraid to admit nowadays. I was once amused to see that St. Robert Bellarmine, another holy cardinal, wrote a book entitled The Art of Dying Well, but now I can’t scoff. Civita made me understand some small bit why he wrote it, and only reinforced in my mind that the timely death of a whole miniscule civilization sometimes is as solemn and pious a passage as that of an aged monk, confessed and pure, waiting for his Redeemer.

I passed through the new town’s cathedral, all imitation purple marble and gilding, a respectable late version of the little village’s shrine, and stood before the silver-encased reliquary of St. Bonaventure's arm in the transept. However, I realized I had seen another reliquary of something perhaps even stranger, a shrine entombing an entire town going to its death with the same eternal grace that conveyed the Seraphic Doctor to his Maker.

Sorry about my disappearance over the last few days. I'd like to give you a colorful story about being kidnapped by the powerful and nefarious P-2 Masonic Lodge and forced to listen to Marty Haugen but the truth's a bit more prosaic. The Internet connection here went on the fritz on Saturday and, this being Italy, just got restored. Expect further details of my various adventures very soon!

Friday, September 19

Viterbo and Bagnaregio were magnificent. At Bagnaregio, I saw the arm of St. Bonaventure encased in silver, appropriately enshrined at his birthplace. While I also saw at Viterbo the wizened but incorrupt body of the town's teenaged patron, the remarkable St. Rose. It was a remarkable glimpse of this young saint of a time far past. Details tomorrow, after I hit a Tridentine Mass at the church of Corpus Domini on the Via Nomentana, which should be extremely blogworthy as it is being said for the repose of the souls of the fallen Papal troops (and their enemies) killed at the battle of Porta Pia in 1870.

Thursday, September 18

Flames in the Darkness of God:

A Twilight Visit to the Chiesa Nuova

The evening of the second Latin Mass I heard at Rome, that wonderful serene evening, I took a long and wandering path home, not quite knowing where I was going nor where I was supposed to go. I found myself, inevitably, back on the Corso, coming out a few steps from the old Oratory, the home of that strange and smiling saint, Filippo Neri, who exalted the humble and cast the mighty from their thrones--by asking his aristocratic charges to follow him about with the tails of foxes fixed to their breeches.

Nobody can hate Pippo Neri, or even dislike him. He is like St. Francis in that respect; those who know him even slightly love him. But what looks like love, in this fallen world, is dangerous. In this misinterpreted and baroque city, love can look like sentimentality, and in this misinterpreted and modern metropolis, sentimentality can look like love. Like so many lovable saints, their affability obscures their holiness, and we love them like we do a senile grandfather.

For example, it's the love-affair that the Victorians had with the little poor man of Assisi that turned him into the shapeless concrete garden knome we all know instead of the fierce Giotto saint who walked on flaming coals before the cruel Sultan. We don't expect sweet little Pippo or his church to be profound. Gentle. Pretty. Cute. Nice, even, but not terrible as an army with banners. But it is. The big-eyed Christ of the Holy Cards should not eclipse the Jesus we see cleansing the Temple of iniquity.

And the Chiesa Nuova, the church of San Filippo's Oratorians, is the church of the saint who was Apostle of Rome, the saint who buried himself in the theologians and philosphers of the Church for three year's study at the Sapienza, not just the sentimental, smiling, bearded grandpa we remember from our childhood books of saints.

There was some traces of the mythical Pippo at first glance. Some descendents of his beloved urchins clustered on the steps playing soccer in the twilight, just like Pippo allegedly once drop-kicked a cardinal's biretta, if I remember the tale right. But beyond the portals of the church was another world. It was dim, half-lit by dozens of gilded sconces down the nave, coronas of light ringing the tomb of San Filippo beyond the east transept. Gilding was everywhere, throwing off sheens of antique gold in the transparent darkness, nighttime cloaking everything but concealing nothing. Dionysian light-mysticism tells us that it is in this Divine darkness that we fully experience God, a very different darkness from the murky gloom of the dim alleyways of our minds.

It was spectacular. San Filippo's humility may have made him opposed to the decoration that later gloriously incrusted the church, but it and only it could truly communicate the overpowering love of the saint. All I could see was the sharp highlights of gold amid the darkness, on the legs of angels, on the polychromy of pillars; everything else was irrelevant. We lose something when we floodlight our churches. The candles of our forefathers were for sight as well as symbolism. Christ, the light, is always represented by the flame of a candle, and St. Thomas tells us that we will see God, not with our own eyes in heaven, but directly in His light, for it only is sufficient.

Pippo knew that candles meant light, but they also meant fire. God is light, represented by a candle, but He is also the fire of the Holy Spirit. Love, real love, baroque love, was fiery. Love is dangerous, not sentimental or trite. It was this that made Pippo into San Filippo.

A few days before the feast of Pentecost, 1544, the birthday of the Church, he experienced a remarkable miracle. A great globe of spiritual fire slid down his throat in a vision and lodged itself in his heart. He was so overcome with fiery love, he threw himself to the ground to cool himself, bathed himself to quench the fire in his breast. Still, filled with great agitation, he discovered his heart had swollen in his chest with a bulge the size of man's fist. After his death long after, an autopsy revealed this remarkable change had broken two ribs, bending them into an arch. Not a single twinge of pain accompanied this prodigy, but forever after whenever he performed a spiritual action, his heart would beat wildly.

It was the church of that great, burning heart, which grew from the silence and darkness of contemplation and the tiny flickering tapers of human love, that I visited. For all the darkness of those massive, cavernous spaces, it seemed familiar as a home, a place of great comfort and love, a love that is so great that sometimes it nearly consumes us with fire.

Another Hiatus

Off to Viterbo and Bagnaregio tomorrow. Both seem to be well-preserved mediaeval cities: indeed, it takes about five minutes to walk across Bagnaregio, about the ideal size for a small town. Viterbo (above) seems to have grown up a little by comparison, though I know her best as the home of St. Rose of Viterbo. This Rose (who predates her more famous namesake in Lima by about four centuries) was a splendid young firecracker of a saint who is best known for having been, at the age of 11 (while dressed in the habit of a Franciscan friar), a street preacher against the abuses of Emperor Frederick II. She, unsurprisingly, ended up as a nun and died at the tender age of eighteen in the odor of sanctity and to this day, her body remains incorrupt. Pretty cool in my book.

I know it's been a thin day for posts, mea maxima culpa. Expect more substantive commentary on mediaeval urbanism, the glories of ice-cream cones and looking at Rome from the inside out, upon my return.

The wonderful Roman appetite for the strange never ceases to amaze me. Maybe it's that, or perhaps they just refuse to give a darn about how strange or silly or solemn they seem. For example, there's an elderly gentleman who, while poor, does not seem a beggar. However, he spends every day inexplicably lounging in a deck chair by the transept of Sant' Andrea delle Valle, a discarded street sign at his side like a warrior's cast-down shield. He doesn't really seem to do much of anything.

Then there's the odd fellow I saw vigorously massaging a fountain last night, or the daring young dandy I saw walking down a sidestreet attired in a cheap rumpled glen plaid suit, white shoes and an enormous straw hat that looked like something straight out of nineteeth-century Cuba. I'm not sure which are dressed stranger: the pale, well-coiffed Barbie-faced mannequins in the windows of the Via del Corso or the reasonably-lifelike women who occasionally imitate them. Or not, as in the case of the gaudy girl in red kneesocks and a perilously short skirt that walked past us in front of the Vittoriano.

You already heard about the pseudo-centurions, of course; I keep running into them, including nearly a whole cohort on the north side of the Forum with their own eagle and I suppose their own Caesar, as there appeared to be a throne but I couldn't figure out which one was Mr. Gaius Julius himself. And then there's the guy in our neighborhood who walks up to girls and screams at them and, his job done, simply walks away. Baroque may be about heathly emotion and intellect, but I suppose it can fry your brain, too.

St. Joseph of Cupertino, unknown date and painter

The Flying Friar

Today is the feast of one of my favorite saints, the humble little priest Giuseppe Desa, better known as St. Joseph of Cupertino. He was not the best or the brightest at first glance, and during his childhood, he was nicknamed bocca aperta or "the gaper," supposedly from his frequent mouth-breathing but actually from the remarkable visions he experienced that no one else could see. But exaltavit humiles and he was truly exalted, both figuratively and literally. He could fly.

He was refused by the Franciscan Conventuals as too simple, while, as a Capuchin lay-brother, his ecstatic levitations made him unsuitable for work. Though actually, he succeeded in airlifting a very heavy cross on one occasion, so I imagine they didn't dismiss him too quickly. He was such a sweet and gentle man (in addition to being slightly distracted) that, after walking through the countryside, he would return with his tunic in tatters, victim to pilgrims preemtively looking for relics.

Such were his virtues he was ordained a priest at age 25, despite the fact he was barely literate. For all his supposed stupidity, he was so filled with the Holy Spirit, he was able to discern the answers to deep and intricate theological problems. This, with his levitations, ecstasies and other phenomena, made him something of an unwitting tourist attraction, and he was fobbed off from one monastery to the next and kept virtually imprisoned in his own cell. Still, he never once complained, and his example of quiet holiness (with remarkable results) remains accessible today. He is patron of paratroopers, test-takers, students, pilots, airplane travellers, air crews and astronauts, and so it should be, for these are all things he no doubt would have gaped at as well.

Besides St. Joseph, we have a few interesting names today. There's the archbishop of Granada St. Thomas of Villanova, the generous "father of the poor." Then there's the Empress St. Richardis of Alsace, wife of Charles the Fat and sister of King Boso of Provence (who?), who once tamed a mother bear and her cub after resurrecting the little bear. Both became her lifelong companions.

There's the Translation of the Relics of St. Winnoc, a Cornish-Breton prince, son of St. Judicael (again, who?), who is depicted in art as in ecstasy while grinding corn. (Trust me, it would take too long to explain.)

Then there's St. Hybald, a friend of St. Bede, who had nothing to do with animals, as far as I can see. Lastly, for the sake of convenience, there are two saints named Ferreolus, one a martyred soldier and the other a bishop, who have nothing in common but the name.

Wednesday, September 17

It seems the Catholic Teen Girl Squad! running joke initiated by this site by a random comment of mine on St. Philomena and then Dan's (as yet unfinished) parody Teen Nun Squad! is starting to permeate the Blogosphere, namely the writings of our very own Holy Roman Emperor, Marcus the First of the House of Shea. Yikes. Or, as Cheerleader would say, "Like, totally."

St. Robert Bellarmine: Great-Grandfather of the Constitution

Today is the feast of St. Robert Bellarmine, the formidable Jesuit-educated cardinal who was both spiritual father to St. Aloysius Gonzaga and who gained Papal approval for the Visitation Order of St. Francis. Most interestingly, for all the fondness historians have for tarring him with the reactionary brush for his misunderstood role in the trial of Galileo (he actually urged against it), his theory of government was one of startling modernity and democracy. He said that authority was vested in the people by God, and it was their consent that gave rulers legitimacy. Understandably, both the kings of France and England were enraged, but it seems that it was St. Robert, not they, who had the last word. He headed the Vatican library and, after dying this day in 1621 (before which he had written a book on how to die properly), was proclaimed a Doctor of the Church in 1931.

On the Franciscan calendar, today is the feast of the Stigmata of St. Francis, though I might be wrong as I have had bad luck with getting the dates right on feasts like this before. Today is also the feast of St. Agathoclia, a martyred slave; St. Ariadne, another martyred slave who was swallowed up by a large rock and never seen again; and St. Columba of Cordoba, a nun (and thus a woman, unlike, say, the Scottish St. Columba, who was not) decapitated by the Moors in 852.

There's also St. Hildegard of Bingen, a fave of mine. The tenth child of her family, she was known as the Sibyl of the Rhine, wrote innumerable hymns, and had seen visions of luminous objects starting at the age of three (after which she slowly figured out this wasn't typical for most people). She also seems to have been the first person ever to devise a "constructed language," beating out J.R.R. Tolkien by about a millenium. Cool.

Great Churches of the World:

Second Thoughts on St. Peter's and the Baroque

I began my architectural meditations this morning on the Tempietto, the symbol of the cool, intellectual perfection of the Renaissance; and I end it at St. Peter's Basilica, another martyrium to the same martyr, the exempluum of the Baroque epoch. I've avoided discussing the great basilica thus far, not in detail, and perhaps it's because I've only been beyond the portals of the church only once this trip for one reason or another. I am afraid not to do it justice; but doing justice to the most famous church in Christendom is something that is very difficult.

St. Peter's is a difficult church, a problematic shrine. Some pilgrims, accustomed to the gloomy (and splendid) solitude of Gothic cathedrals or the antique coziness of the churches of the American heartland (or even, perhaps, the chill airplane-hanger church down the street), find it leaves them cold. And as I said before, emotionally, it is a monstrous, cavernous building at first glance.

However, such thoughts fail to understand the essence of this glorious church. Nobody has ever truly seen St. Peter's; it's too familiar to be seen. Our notions of it are already present by pictures in art books, our love or our contempt for the Office which it represents, by crude elevations on dog-eared holy cards that show Maderno's "incorrect" facade overshadowed by St. Joseph as patron of the Universal Church.

The problem of coldness is a difficult one, but at the same time is something of a straw man. St. Peter's is not a building for the faint of heart precisely because it courses with emotion, whatever the size or scale. It is baroque, and the baroque is the marriage of feeling with intellect. Every detail of the structure, from gargantuan Solomonic column to the tiniest gilt-headed cherub, is meant to engage us subjectively and pull us finally towards an intellectual, objective truth, the glory of God, the subursted dove of the Holy Ghost we saw so palely before in the dome of the Tempietto. The baroque is a prophesy of John Paul II's phenomenology, where the objective truths resonate in our subjective souls.

We don't understand the baroque today because we don't understand emotion. I even made the mistake myself, somewhat in reverse. I neglected the Roman architecture of the era as too classical and conventional. It isn't, trust me: you can't call anything that produced the sacred mystical-marital bliss of the Ecstasy of St. Teresa staid. Instead I looked towards the whimsical pastels and stucco filigree of the stage-set churches of Bavaria and Latin America as the real essence of the movement. While splendid, these more eccentric outliers miss the point as well.

The baroque is derided as sham architecture, plaster and chickenwire patched up with gilt. But just as often, it is an architecture of polychrome marble and pockmarked travertine. Baroque is solid. Baroque is marble. At her heart, she is stone, not plaster. She is not caprice and whimsy (and thus a sham), and since we have elevated fickleness and crowned her as the queen of our false emotions, we can only assume an art based on an appeal to hearts and minds must be mindless, that an art based on leading us to truth must be necessarily untrue.

Nothing about the interior, the gesticulating bronze bishops and innumerable marbles is fickle or cold, two extremes of the same lie about the baroque. We're afraid to respond to the baroque: it seems cheap, theatrical, undecorously happy, and thus false, immoral. But we forget that even if the happy angels were perhaps feigned, the smiles on men like the laughing St. Philip Neri were not.

Great Churches of the World:

Bramante's Tempietto

The Tempietto di San Pietro in Montorio is by far one of the most perfect buildings ever conceived by the mind of man: the first truly all' antica building of the Renaissance, so brilliant that it was the only modern structure to be included in Palladio's and Serlio's treatises on Roman architecture. That's the official story, anyway, and with an introduction like that, it would seem disappointment is inevitable.

However, my visit to the tiny shrine, a martyrium bearing witness to the legendary site of the inverted crucifixion of St. Peter, proved that nothing is ever inevitable. We had spent the day, as always, on a long lecture-hike around Rome discussing the Quattrocento, and this was journey's end. I can't think of any better way to experience it.

The first thing a traveller notices is that San Pietro, the adjoining parish church, is the site of the Spanish Academy in Rome. Indeed, this quintessentially Roman oratory is a monument to the piety and glory of the Catholic Monarchs Fernando and Isabel, who, celebrating the splendor of their newly-united Christian Spain endowed this elegant reliquary in stone at the close of the fifteenth century, under the pontificate of the Spanish Alexander VI. The eagle of St. John and the lions and castles of Leon and Castilla stud the restrained stained-glass of the little church, but the building itself still points indelibly to the Prince of the Apostles commemorated within.

It's also extremely small, setting you up to disregard it as an oversized model; a stone version of some immense Italian tabernacle too little to be a building, too big to be a piece of sacred furniture. Don't be fooled.

It is a triumph of Christian humanism: the pagan form of the round temple, the tholos is transformed into a shrine of witness, with the stalwart Doric columns of a warrior-god becoming signs pointing instead to the fortitude of St. Peter, a warrior by his conquest of the crown of martyrdom. Doric was said by Vitruvius to be the most difficult of the antique orders to proportion, with its curious triglyphs and metopes, and Bramante's own triumph is here by using it with such elegance and perfection. Nearly none of the contradictions inherent in that style of architecture can be glimpsed.

Around the frieze, above the perfect number of sixteen columns, run the emblems of the liturgy: incense boat, Gospels, cross, aspergillum, torches, replacing the ewers and sacrificial knives on the portico of another perfect round structure, the pagan Pantheon. All is restraint and balance: as opposed to the dramatic contraposto of Baroque architecture, we see the smoothness and ease of Renaissance intellect, a Palestrina motet in stone.

Within, in the tiny sixteen-foot-wide sanctuary (no bigger than the oculus of that same Pantheon) there are traces of opulence and even, at first glance, gaudiness, as fragments of riotous frescoes, moldering in the darkness, still cling to the encircling architraves and the eight pilasters (a halving of the outer sixteen). Overhead, the wooden inner dome is studded with gilded stars, and the ghostly outline at the apex of what might have once been the dove of the Holy Spirit. But even then these bright colors, dimmed by age, have elegance to them, no curve of the painted fretwork without its symmetrical counter-curve, no color without its complement.

We were all crowded in there, listening to Professor D. lecture. I pretended to look down through the inset grillwork into the crypt and knelt at the altar's predella. And I considered the marble St. Peter before me, enthroned and aureoled by an enormous carved seashell, and thought that only the sacrificial triumph of the first Pope was worthy of this triumph by the first authentic architect of the antique revival.

Tuesday, September 16

Most prominent today among the saints commemorated are St. Cornelius and St. Cyprian, respectively pope and bishop. Pope St. Cornelius was elected in a period of fierce persecution, when the possession of the Keys of the Kingdom was in all likelyhood a one-way ticket to the Mamertine prison, and also had to cope (or shall I say pluviale?) with the severe Novatianist heresy, which didn't like admitting repentant heretics into the Church. He was exiled and martyred after less than two years on the throne of Peter and is buried at San Callisto in Rome. He is patron of epileptics, cattle and domestic animals, and is invoked against twitching and earache. His emblem is, among other things, a cow. Please do not confuse him with the character in Planet of the Apes, or with alchemical kook Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa von Nettesheim (whose birthday was, incidentally, two days ago) or elephant King Babar's favorite General (long live Babar, long live happiness, of course).

His companion in the feast, St. Cyprian of Carthage, is not to be confused with the apocryphal ex-sorceror St. Cyprian of Antioch, who is, like so many fun saints, no longer on the calendar: before converting, he was said to have written a grimoire and lived in some sort of undersea cave, unless I am confusing him with someone on the Arabian Nights. I think that's right. His own (supposedly suppressed) cult is popular in Portugal for rather shady reasons, and also has given rise to a magical-miraculous chain letter of some sort. But back to our own saint of the day, who was not a magician, mercifully, nor a Novatianist. Still, today's St. Cyprian still took a rather severe view on penitence. He said that penitents should be admitted, but not after making them sweat a bit, and only under the most extreme conditions. Probably something involving the infamous tortures of The Comfy Chair and the Soft Cushions. (I make joke.) He had a habit of annoying St. Cornelius, though doubtlessly with the best intentions. He was decapitated on 14 September 258, and is patron saint of Algeria. He also seems to have written a prayer for jailers and their captives.

Besides these two holy bishops, there are on the calendar today St. Curcodomus, a Benedictine abbot and St. Dulcissima, the virgin-martyr patroness of Sutri in Italy of whom nothing is, as usual, known. More intriguing is St. Edith of Wilton, the illegitimate daughter of St. Wildfrida, and who was born, was raised and died in Wilton Abbey, of which her mother was abbess. She started out as a teenaged nun and died at the age of 23 on 14 September 984. In between being admitted to the order at age 15 and dying less than ten years later, she was offered the title of Abbess three times and turned it down three times. After dying, she is said to have smacked the devil on the head. You go, girl. Dan, I'd say she's a good candidate for patroness of the Teen Nun Squad, no? Also, there is St. Ludmilla of Bohemia, grandmother of St. Wenceslaus, who was strangled by assassins on 15 September 921, and is patroness of duchesses and in-law problems. Lastly, there are the two Spanish martyrs, St. Rogellus and St. Servus Dei, which you have to admit is a pretty sweet name.

Monday, September 15

Not every day can be Sunday, just as not every liturgy can be a solemn one, that grand Platonic High Mass from which all liturgies derive. I sprinted down to San Gregorio ai Muratori this evening after an exhausting day of touring-lecturing. I was there for a Latin Mass in honor of the feast of the Seven Dolors, not quite knowing whether to expect chant or hymns in honor of the holy day or a heartfelt but severe and rushed mass as I had witnessed yesterday in Trastevere. It was, as I discovered, another Low Mass, but it proved to be one of the most memorable spiritual experiences I've ever had. San Gregorio is a tiny church tucked into the lowest story of a humble Roman palazzo-turned-apartment at the end of a twisting cobbled street cluttered with parked bicycles. Only a miniscule bell-cote over the restrained, soot-shrouded classical portal marks the chapel's purpose. Within, the grime of ages masks its walls, filled with funerary monuments, two side altars, and the devout clutter of an indulgenced cross and a baroque confessional, but the innumerable Renaissance reliefs are still touched with gilding and glitter in the semidarkness. A dim oil painting of St. Gregory in supplication to the Virgin looms above the principal altar's six heavy brass candlesticks. It is a church filled with the delicate decay of its own forgotten history waiting to be discovered.

There were only a handful of us there, kneeling in those warped, baroque pews, and I would be grateful for the experience of this sacred intimacy. The priest, vested in white, entered to the clatter of the sacristy bell, his hands reverently holding the unconsecrated host beneath the heavy white chalice veil. The cassocked acolyte gracefully received the priest's biretta as he entered into the sanctuary beyond the marble altar-rail. The ancient Latin prayers were recited slowly and limpidly in his gentle baritone, in a solemn tone tinged with mournful introspection. They were accompanied by the effortless gestures of genuflecting and crossing, and the attendant's gracious oscula, the long-lost liturgical kiss of Trent, on the cleric's hand, on the biretta and on the cruets, as sacred objects passed between the two of them. Though I knew the ritual gestures were complex, it looked as beautifully simple and unconsciously natural as the first time Abel offered his sacrifices to God or when a child knees to pray at his bedside. This was the "noble simplicity" liturgists have failed to find for the last fifty years, despite the differing abuses heaped on the old rite by modernists and hurried, harried Hilaire Belloc 20-minute-Mass priests alike. Even the silent Canon, which sometimes seems to me like a veil drawn pointlessly over the transparent beauty of Christ's words, seemed transcendent, as half-glimpsed gestures told the whole story of the unspotted Sacrifice.

If we can't have Palestrina and incense at all our liturgies, we can still have these small beauties to comfort us.

I left with a wistful smile on my face, watching the sky in the east mellow behind bulbous, half-Austrian belfries, fantastic chimneypots and the wiry scarecrows of television antennas, which are graceful even in Rome. I strolled leisurely down the streets near the Ponte Sant' Angelo, watching the sunlight die on the dappled, dilapidated stucco as antique dealers in Via dei Coronari shuttered their storefronts. Behind the glass, I glimpsed dozens of navigational instruments in glittering brass, miniature obelisks covered in hierogylphs, huge marble pagan heads on pedestals, armillary spheres, scientific lenses.

I was so serene from the Mass, in fact, I nearly walked into a parked motorino while rubbernecking at some wooden liturgical candlesticks in the window of one shop. I'm quite hopeless, really.

Pietà, Michelangelo Buonarroti, 1499

Today is the feast of Our Lady of Sorrows, also formerly called the Seven Dolors of Our Lady, the principal patronal feast of the University of Notre Dame's Congregation of Holy Cross. The feast has its own litany and chaplet, that of Our Lady of the Seven Sorrows, which seems to have an association with the Servite Order. Indeed, the Servite's feast on September 15 is the origin of the current commemoration on the calendar, as formerly the feast fell variously on the third sunday of September and also during Lent. The Servites also comemmorated it on July 9 in their own calendar. The Seven Sorrows were events throughout the Virgin's life, beginning with the prophesy of Simeon Senex, while Our Lady of Sorrows seems to have more of an association with the events of the Passion of Christ (particularly through many famous images showing her cradling the lifeless body of Her Son), though Her heart is nonetheless shown pierced by the seven swords of the Dolors.

Today is also the feast of St. Adam of Caithness, a Cistercian bishop burnt to death by his parishioners after raising their tithes, and who never seems to have been officially canonized. After him are variously a St. and a Bl. Aichardus, both monastics, as well as St. Catherine of Genoa, who had a vision of Savanarola in glory and is the patron saint of a friend of mine's car, and is shown (in a portrait by the female artist Tomasina Fieschi) having been a slight woman with a long, patrician nose; prominent cleft chin, smiling, broad but thin lips; high cheekbones; and large dark eyes punctuated by thin, graceful eyebrows. She also seems to have had laugh lines, though I don't see them in the picture, which frankly makes her kinda scary-looking despite that appealing catalogue of features. She is patroness of those ridiculed for their piety.

On the calendar today are also a St. Emile and a St. Jeremy, both from Cordoba; St. Nicetas the Goth, presumably the patron of black lipstick and body piercing; and the martyr St. Nicomides of Rome, whose emblem is a spiked club, which sounds kinda Gothic as well.

An old image of the Tridentine Rite being celebrated

Six Degrees of George Rutler

I had a bit of a Tridentine marathon this morning after narrowly managing to miss the Latin Mass twice within the period of an hour, and then ending up at a church in Trastevere where the priest and congregation were out on the street waiting for a bunch of Guatemalan pilgrims to finish up their (remarkbly raucous) services in honor of their independence day.

San Gregorio ai Muratori (staffed by our good friends from the Priestly Fraternity of St. Peter) was the first parish I stopped in. Things got off to a bad start when I misread the schedule and thought they had a polyphonic mass at 10:30 after their usual mass at 9:00--which was in progress. San Gregorio is a tiny, tiny church built into a wall at the end of a narrow sidestreet near the Corso, and frankly I think the only place they could fit the choir is velcro-strapped to the ceiling. Still, it's a very pretty little Baroque oratory. It's the most Tridentine of Rome's parishes, what with being served by the Frat.

Not being the wiser, I returned at 10:15 after pottering around the Corso for about forty-five minutes (including standing in front of the other, much grander Tridentine church in Rome, Gesu e Maria, and watching the cassocked seminarians wander in for their 10:00 mass). Naturally, I found the church locked and the sacristan getting into her car. She was a careworn woman in her mid-forties, still rather handsome, and spoke English very well. She directed me to a parish in Trastevere whose name escapes me at the moment, for their 11:00 Latin Mass. So, still eager not to miss my last chance for the old rite this Sunday, I hotfooted it over there in coat and tie, only to find, like I said, most of the parishioners waiting out front while maracas clattered garishly inside. I had a few words with the cassocked priest, an eager Estonian seminarian in a plaid shirt and a bearded old man in a ratty sweater I'll call Mr. C. More about him later.

This is the second time I'd seen the old rite in person, and there was a good turnout in the pews, both young and old, though no families with children as far as I could see, which struck me as curious. It was quite lovely, though ceremonially it was the lowest of Low Masses. Though it wouldn't kill them to get a cassock and surplice for the sexton instead of him traipsing around the sanctuary in a green sweater-vest. On the other hand, he seemed a reverent sexton. We, rather than this impromptu acolyte, made most of the responses, however, but at breakneck preconciliar speed. The priest preached a vigorous and very good little homily on the feast of the day, while gesticulating with an appropriate and huge bare cross, something I will never forget. I was able to understand quite a lot of it. His gestures throughout the Mass were quick and lively, and I would go as far as to call his Latin delivery, like I said, as distinctly rushed. 1950s liturgical deja vu, though with better architecture: the church was luminous with pale baroque stucco-work, the only light coming from candles and the enormous clerestory windows overhead. The Salve Regina at the end was touching, but the braying chant tone sounded like something out of the old medieval Donkey Mass of Christmastide, where all the prayers ended with a loud and mule-like cry of "ter hinhinnabit!"

Still, it was worth the walk, especially since afterwards I had a long talk with the priest, Fr. I., a Uruguyan cleric who had studied at Dunwoodie in New York and knew both my professor Duncan Stroik and Dan's hero, Fr. Rutler. He even looks a little like him. The funniest thing is that when I met Fr. Rutler, he knew my other professor, Thomas Gordon Smith. Fr. I. seems a very good priest, and not too shrill as are most traditionalists of his age group. I might drop him an email sometime.

One of his close friends was the abovementioned Mr. C., an elderly gentleman who writes for an oddball American Catholic periodical whose name you'd recognize, as it rhymes with The Launderer. When he introduced himself as the Rome correspondent for this publication I knew there wasn't going to be a dull moment for the next hour. This is, I suppose, the one problem with the Tridentine rite, as it attracts both Catholic Nerds and eccentric cranks. Mr. C and his lady wife are both fascinating folk, but perhaps rather on the dour end of the traditionalist scale, with a head-full of odd ideas. For one thing, he (and Fr. I.) really seem down on seminarians spending their time in choir for the recitation of the Office, claiming it's too monastic. Seminarians, apparently, receive too much choral education--not a problem, however, with Fr. I., judging from his recitation of the Marian antiphon.

I think this is an example of the unfortunate tendency towards what Fr. Jim calls a "Low Mass mentality," something one sees particularly among older members of the Latin Mass movement. Indeed, in Continental Europe, massive choral celebrations of the Sacrament in either rite, as at the Oratory or St. John Cantius seem to be rare. The closest thing here seems to be at Gesu e Maria parish, whose mass usually includes multiple assisting clerics, a chant schola and organ accompaniment. Indeed, the Estonian seminarian I met was lauding the sizable resources of the American Latin Mass movement and saying that in the U.S. it was "a great moment" presently for the Tridentine rite, somewhat disorienting to hear. I imagine it's a sliding scale.

There is also, of course, the occasional specter of political crankery associated with Continental traditionalism, as I saw a poster on the church door advertising a semi-monarchist youth group meeting under the Sacred Heart emblem of the old Vendean rebellion. I have a nostalgic love of monarchy but it's not something that would drive me to sign a petition, and it doesn't help the movement look fairly respectable. Of course, in Italy, royalism and legitimism have started to come back out of the woodwork as a consequence of regional disturbances, and even the centralized monarchy of the Savoyards has only been dead less than sixty years. People in Naples, for example, have started to look lovingly back on the days of the Bourbons, when they were still dirt-poor but at least independent of Rome. I even saw the full royal coat of arms of the Two Sicilies on a motorino decal the other day. Still, Mr. C. and Fr. I. didn't get into that.

That being said, I think Mr. C. didn't disapprove of me, and he's not completely a kook as he spoke highly of Vatican II, and could have been far more shrill. At least Masonic conspiracies didn't come out of the woodwork. Though, probably there are those of his stripe who would dismiss younger Catholic Nerds such as my fellow Whapsters as too flippant. He's not a Lefebrist, mercifully, and I have plenty of cranky ideas myself, I just never let them out of their cages. Don't get me started on mitred abbesses or sackbutts.

Still, I hope my tales of Catholic nerddom at Notre Dame gave him some hope, though I imagine the freewheeling humor of the Shrine would probably be beyond him. As someone who belongs to no real faction in the Church and who moves with relative ease between friends who are variously orthodox supporters of the Novus Ordo, devout Charismatics, unsmiling traditionalists (who don't read this blog), Catholic Nerds of all stripes and your typical St. Astrodome's parishioners, it's inevitable for me to find crankery somewhere in any group.

Now, I'm not sure I want to make this Trastevere parish my home for the next year, and I plan to continue going to our English class mass at Sant' Eustachio in the evenings--as well as perhaps one of the Tridentine masses in the morning--but it was a pleasure to meet some fellow English-speaking Catholics, even if their perspective on tradition is perhaps slightly different from my own fairly "conservative" tendencies. I'll drop back sometime probably--they were very hospitable, after all--but I'd also like to go to mass at Gesu e Maria and San Gregorio first. Little San Gregorio has a certain intimacy I could come to love, while Gesu e Maria seems to have the most elaborate Tridentine liturgy in the city. Furthermore, the clergy are younger, and I'm curious to see how young people besides myself react to the old rite. If there is a future for the old Mass (and I hope there is), it is with those eager young seminarians vested in cassock, fascia and cappello romano I saw bounding up the steps at Gesu e Maria, rather than with the curious denizens of Trastevere.

Still, there's something to be said for hearing mass said by a Uruguyan traditionalist who uses props in his homilies.

Sunday, September 14

Opening Hymn: Lift High the Cross (Crucifer)

Gloria: New Mass for Congregations, Andrews

Responsorial Psalm: Do not forget the works of the Lord, Batastini

Offertory Anthem: Let This Mind Be in You, Hoiby

Sanctus, Memorial Acclamation, Amen, Agnus Dei: Mass For the City, Proulx

Communion Antiphon: I give you a new commandment, Willcock, S.J.

Communion Motet: Ave Verum Corpus, Mozart

Closing Hymn: Take Up Your Cross (Duke Street)

Saturday, September 13

Trastevere after Dark

Words Exchanged with a Lady Scottish Book Merchant

I had a long walk in Trastevere this evening which lead me to The Almost Corner Bookshop in Via del Moro, a delightful little establishment crammed wall-to-wall, and then some, with an excellent selection of English-language books. I could have spent hours in that single, pleasantly cluttered room, running my eyes over the shapes of the letters, thumbing through the eternal piles of paperbacks neatly littering the floor, listening to the hum of revelling pedestrians in the growing darkness outside. It is, by far, one of the best small bookstores I have ever seen, with a marvelous selection of classics, history, art, architecture and fiction that is, in many respects, much more selective and far better than any Barnes and Noble. I spent a good thirty minutes standing by the fiction shelves, paging through translations from Portuguese and Spanish and Italian of authors I had never met before, wondering at the splendid plots their books contained, at future conquests for my library, at what I might like to read over dinner, as I had struck out on my own.