Tuesday, January 6

S. Peter of Verona, Martyr of Lombardy

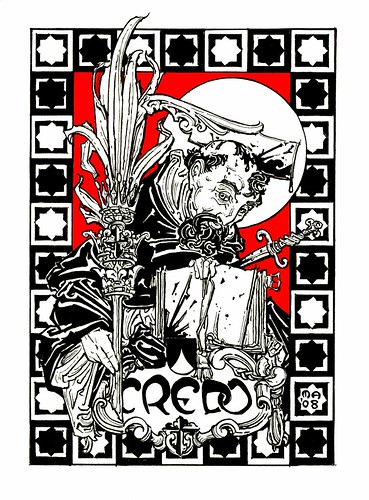

Matthew Alderman. S. Peter Martyr. 4" x 6", ink on vellum. September 2008. Private Collection, Virginia. (Click image for larger version).

A work commissioned by a client (and friend) in Virginia as a Christmas present for her younger brother, whose confirmation saint is S. Peter Martyr.

Her response: "A perfect balance of blood, awash with profundity and Dominicanism!" (She's a writer. They're allowed to say stuff like that.)

She reports on her brother's reaction: "He has been showing it off to anyone who will listen as 'the best gift of the entire year'!"

Which comes, not so much as a puff-up of pride, but a great relief! The artist always risks getting boxed up in his subjectivity if he is not careful. Admittedly, so long as it is directed by a properly-formed conscience and a deep artistic sense of decorum and precedent, this subjectivity is one of the artist's great assets. However, he always runs the risk of ruining that particularly valuable facet of himself by falling into egotism. Such comments, and such abilities to bring a little modicum of happiness, always come as a great relief as a result! Especially if the work, true to traditional iconographic form, involves a gory meatcleaver.

The story of S. Peter Martyr runs thus:

Born at Verona, 1206; died near Milan, 6 April, 1252. His parents were adherents of the Manichæan heresy [ie, Cathars or Albigenses, those sexually-repressed, suicidal dualist weirdoes so beloved of sub-Dan Brown fictioneers], which still survived in northern Italy in the thirteenth century. Sent to a Catholic school, and later to the University of Bologna, he there met St. Dominic, and entered the Order of the Friars Preachers. Such were his virtues, severity of life and doctrine, talent for preaching, and zeal for the Faith, that Gregory IX made him general inquisitor, and his superiors destined him to combat the Manichæan errors. In that capacity he evangelized nearly the whole of Italy, preaching in Rome, Florence, Bologna, Genoa, and Como. Crowds came to meet him and followed him wherever he went; and conversions were numerous. He never failed to denounce the vices and errors of Catholics who confessed the Faith by words, but in deeds denied it. The Manichæans did all they could to compel the inquisitor to cease from preaching against their errors and propaganda. Persecutions, calumnies, threats, nothing was left untried.His murderer later became a Dominican laybrother himself, and is venerated as Blessed Carino of Balsamo. (It was a popular cult and it is unclear to me if it ever got approved by Rome, as the paperwork got lost at some point. Really.) His accomplice, Manfredo, lighted off for the Alps and took refuge with the Waldenses, an obscure proto-Protestant sect founded by one Waldo (really), who are now best known for renting out their space in their small number of Roman churches to touristy opera concerts.

When returning from Como to Milan, he met a certain Carino who with some other Manichæans had plotted to murder him. The assassin struck him with an axe on the head with such violence, that the holy man fell half dead. Rising to his knees he recited the first article of the Symbol of the Apostles, and offering his blood as a sacrifice to God he dipped his fingers in it and wrote on the ground the words: "Credo in Deum". The murderer then pierced his heart. The body was carried to Milan and laid in the church of St. Eustorgio, where a magnificent mausoleum, the work of Balduccio Pisano, was erected to his memory. He wrought many miracles when living, but they were even more numerous after his martyrdom, so that Innocent IV canonized him on 25 March, 1253.

Peter's dying witness to the faith handed down to us by the Apostles later inspired a party snack of mine, incidentally. (Look, we're Catholic. Some of us think stigmata cookies are a good idea. We smile because the saints are joyous in heaven, and perhaps the ketchup reminds us we're called to nobler sacrifices.)

Back to the drawing. A finished work is never perfect, and the artist always feels his greatest project is the one next up on his drawing board. There are always problems, things you'd wish you'd been able to fix, rework, or study more carefully, as well. On the other hand, dissatisfaction or even failure can also be remarakbly salutary as well, as while liturgical art can exhort and challenge the faithful to remember the suffering of the martyrs--and thus have a certain positive hagiographic shock value--you have to at least get your foot in the door first with beauty, tradition and a sense of psychological complexity when the subject demands it. Or perhaps, depending on the audience, the splatter comes first, and then the serenity.