Tuesday, August 15

To arbiters of ecclesiastical tastes, whether Gothic or classicist, the Bavarian rococco may seem just a little too much. I was once told by a young lady (herself feminine and sensible, no tomboy at all), that it was too girly, too bouncy pink-and-white, to really work for her. Other women have said just as much to me when it comes to the more flowery, embroidery-sampler bits of popular piety, the pastel-hued version of Rome's agressive crimson and gold. Sometimes it can make a fellow cringe, for sure, and desire stronger and more ferociously Byzantine Christs. I myself prefer the more sober muscularities of the Roman baroque, expressive the majestic, strong, perhaps even fearsome femininity of Mother Church rather than her more youthful, maidenly aspect.

But Mother Church, and Mother Mary, have their ebullient girlish side, too, for sure, and these explosions of splendid gilding and sentimental cherubs are not without their glories, either, reminding us of the explosions of pure joy deep in the Christian heart. The rococo speaks to that that delirious, giddy, even slightly silly bit of Ecclesia that, when reunited with her heavenly lover on Easter even, declaims the out-of-control extravagances of the Exsultet with its happy faults and rejoicing bees. (It helps that Mass is said in such places, no doubt, by burly, stubborn, and brawny German clerics intoning the Ordinary with stentorian bull's voices, to balance the equation properly between male and female.)

Can we imagine a young Virgin laughing? Perhaps we ought.

We see Mary in her old age at the Assumption, laid out on her deathbed with the heaven-sent palm and the apostles all around her, but we also see her as she was at the Annunciation, a girl, quiet and sober, yes, but still a little slip of a creature who was by today's standards more a kid than a teen--and in spite of that, was ready to take on the burden of the Godbearer with the assurance of Divine Will. Today she is the old woman reunited with her son, and today she is also the sweet young princess poised on the edge of the eve of her Coronation, pure youth, pure femininity, preparing to make that shift to become the reigning queen, and queen mother at that, embued with heavenly glory, the queen standing at the right hand, arrayed in Gold, as the Psalmist says, the presence of whose beauty is desired by the King, her spouse the Holy Ghost.

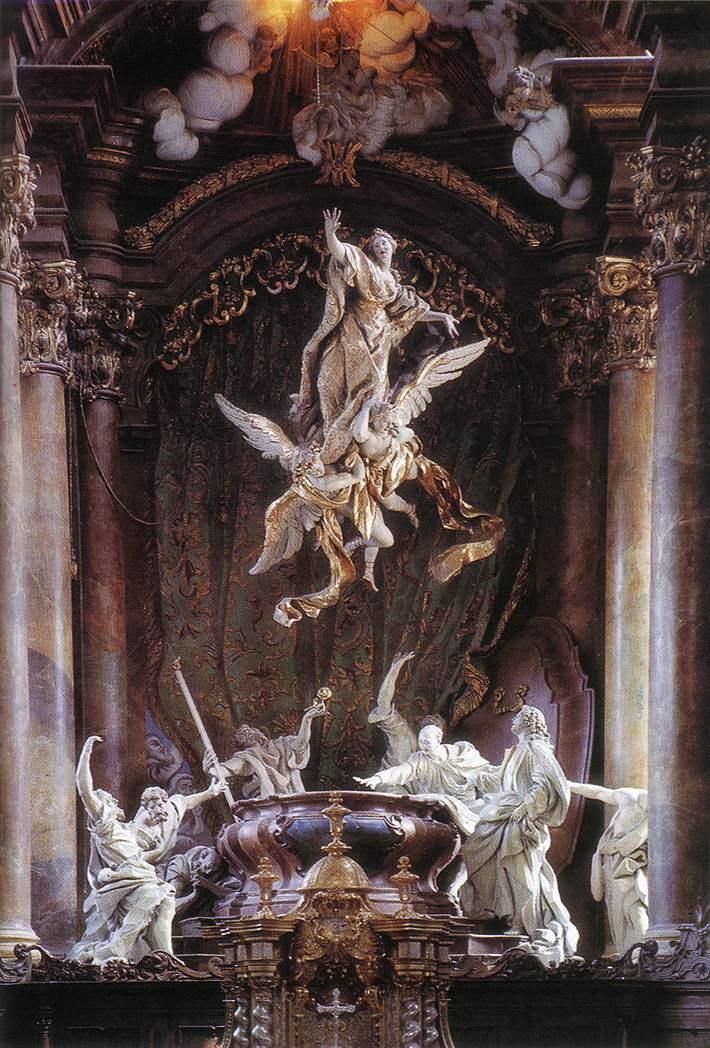

And yes, in the altarpiece we see above, by Egid Quirin Asam, it does all look a bit theatrical, a bit operatic, a bit louche to twenty-first-century eyes--but God is indeed the greatest showman, the greatest maker of spectacle and theater, who plunged into the action of the play after the characters he created had made an awful mess of things, as Chesterton once wrote, and who reminded us of the showy glory of the body in such festive and seemingly superfluous flurries of glory as the Ascension and the Assumption--superfluous until you recall of the Resurrection of the Dead, the life of the world to come, and the encounter with pure beauty that will accompany it. There ought to be no shame, no theatricality to this divine theater of signs. This extravagance is perhaps not for everybody and all times, but worth our consideration all the same.

So rococo is a bit on the girly side, and a bit theatrical. But it's yet another of the many architectural windows into the interior mind of the Church--at once heavy and masculine as Christ in the tomb, in the Romanesque, as youthful and beautiful as the young apollonian Christ of the Catacombs, as maidenly and mild as the annunciate Mary, or as formidable and grandiose as the woman clothed with the sun. She is all those things, as universal and yet distinctive as each and every of the unique saints that are her children.