Monday, August 30

Processions at Mass

One of the most significant impressions my first Tridentine Low Mass had on me was the economy of ceremonial in the old rite. There was a strong and undilated dignity about the way the priest seldom strayed from the altar, moving only side-to-side with a peculiar and dignified shuffle from Epistle to Gospel corner. The tabernacle was right there in front of him, God literally in your face, and so there was little need for the repeated slouching crossings of the sanctuary or knots of Eucharistic ministers so common today. With the Mass cards, he had everything at his fingertips, and there was none of the frantic page-flipping, botched memorizations or book-juggling so common in parochial celebrations of the current Rite.

There's really no reason that the ornate simplicity of the priest's gestures and posture can't imbue celebrations of the current rite and serve, perhaps, as an inspiration for a future revision of ceremonial. It weds various ceremonial gestures quite fixedly to certain parts of the mass, giving a sense of permanence unlike today where there are, for no good reason and quite in contravention of the rubrics, ten different ways of making the long-standardized orans gesture. Indeed, the more I think about it, the more the old rite, properly done, seems to be a practical benchmark for the noble simplicity which is called for by the current documents.

The Low Mass, of course, is not the perfect, or normative, mass: that honor goes to the Solemn mass in all its forms, both pre- and post-Conciliar, and even the present rubrics (such as those given in the present Caeremoniale Episcoporum) recognize the importance of pulling out all the stops for a Solemn Pontifical Mass. While, sadly, such venerable and harmlessly beautiful customs as the bishop's private candle-bearer, the pontifical gloves, and the bishop vesting at the altar, seem to be absent, there are nonetheless glorious rubrics calling for as many as seven candle-bearers (!), the wearing of an episcopal dalmatic beneath the bishop's chausible, and as many as four deacons, two to assist the bishop and two to assist at mass. I've never seen a mass done that way, but there's nothing legal stopping it from happening in every cathedral in every diocese in the United States. This 'noble simplicity' is a world away from the fantasies of Dick Vosko and Edvard Sorvik, and seems to tremble excitedly on the verge of spilling into full-blown clerical baroque with the addition of just a few more sentences here and there.

What distinguishes the Low Mass from the current parish mass is it knows, rubrically, how much it can handle: it does what it does well. It is a model for the sort of liturgy perfect for a contemplative weekday, and its sense of gravity is perfect for Sunday as well. It is, however, without some celebratory additions, not suitable for any given Sunday: though the full-blown Solemn High of the Old Rite is also beyond the needs of many small parishes. The present rubrics allow, quite brilliantly I think, the introduction of 'high mass' customs into what might have been a silent Sunday Low Mass, such as incense, a processional, hymns and the sung ordinary of the mass.

However, few have seen the genius of this idea and instead we have, in many cases, a Sunday Mass with the same lack of liturgical splendor of a Tridentine Sunday Low Mass, but without its rubrical economy: while there was a quiet grandeur to the solitary priest with the server, it seems gone today when servers wander all over the sanctuary in elaborate and redundandly aimless loops. There's no reason this has to be, even if the current rubrics remain unchanged.

First, sanctuaries should be designed to be more compact, unless, of course, the priest is willing to use a large and spacious sanctuary to his advantage. At the Indult parish I attended in Rome, I was actually much closer to the priest and altar than I would have been in my home parish, with its versus populam altar. Compactness allows the undignified spectacle of large and aimless and unceremonialized processions to the tabernacle and the ambo. Admitted, the current rubrics require some walking, such as at the Gospel and the readings, which is a dignified aspect of the current rite, or with the collect read from the priest's sedilia, which I think probably could be restored to its former position at the old Epistle corner of the altar. However, a small church where grand ritual will be rare should attempt to minimize those long and empty distances.

That being said, a grand church by nature will have a vast sanctuary: and it should learn to use it to its advantage. Processions are certainly in keeping with the new rite, and, gilded over with the pomp of the old, they could be magnificent. At present, St. Peter's retains the custom (seen often in medieval liturgies) of stational processions around the church, prayers at side-altars, and incensations, proceeding some solemn vesperal services.

This, in microcosmic form, is a model to the medium-sized or large parish or Cathedral where solemnity should be more pronounced. The Gospel procession, which is solemnly ceremonialized with much dignity here at my home parish of Notre Dame, is an eminent example of such a practice. Lights, incense, even banners, would be fitting for such a procession: and as a procession, it really ought to go somewhere more than just the shortest distance between two points. Perhaps one could circle the altar, or run round the rim of the sanctuary. It's more a matter of aesthetics and good taste than simple rubrics.

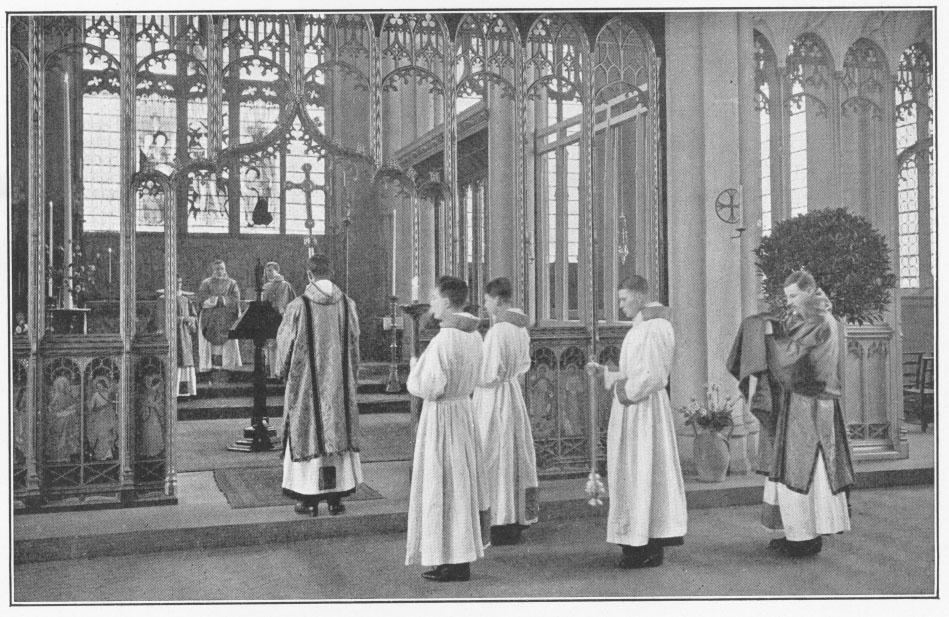

The same should go for the Offertory Procession. More often than not, this is a rather undignified knot of underdressed laymen and women who wander up the main aisle, a world away from the medieval precedent cited to revive this fitting custom. The custom of some high-church Anglicans--who often cite the procession-loving Sarum rite for the source of their revived practices--might be worth considering at this point. In some cathedral churches, several servers retire to a side-chapel and bring up the unconsecrated species in a veiled chalice accompanied by lights, a crucifer and an incense-bearer. Should laymen wish to accompany this procession, they could easily carry up the basket of alms often included in many present-day offertories. But no tank tops, shorts, or flip flops.

Should the priest be required to return to the tabernacle (say, at an altar of reservation in the apse) from the altar of sacrifice, it should be given some measure of dignity. At Notre Dame, when the unused Hosts are taken up from the Communion ministers, they are returned to the tabernacle accompanied by two taperers, a laudable custom indeed.

Another point, I think, worth mentioning, is the current state of the entrance procession. This has often necessitated the awkward placement of the sacristy either in the west end of the Church or the addition of a duplicate and wholly unnecessary vestry, often in a disused side-chapel. This is wholly uneccessary. It would be far simpler to process in from the sacristy behind the sanctuary--which is often provided with a door into a side transept for easy access--then loop around a side-aisle to the back and turn to the front.

This once again revives the ethos of the medieval procession in a simple and dignified manner, allows all those hymn verses to be sung without the priest standing around doing nothing at the sedilia, and I have seen it done to great ritual advantage both in Rome, at the church of Santa Maria Sopra Minerva, and also at my home at Notre Dame on Sundays when it is too cold to sneak outside the church and pop into the narthex. It prevents an undignified traipse to the back from an east-side sanctuary, and also frees the parish from having to add yet another room to a parish already crowded with cry-rooms, reconciliation chambers, and Eucharistic broom-cupboards.

Small churches may not be able to fully approximate this ideal. In some cases, it might seem rather contrived, as in miniscule daily-mass chapels which is why I suggest these only for high feast days in medium-sized or large churches. Certainly, at simple masses, servers should be trained to take the shortest path between two points, and effort should be undertaken to determine the best way of doing it, as well as teaching them some measure of dignified bearing. And while vast processions--or even simple ones--might be beyond the abilities of some parishes on Sundays, they should remain an ideal, and the movement of the priest and his assistants around the sanctuary should be treated as ritual rather than mere pragmatism. Noble simplicity does not mean sloppiness, and it also means, if you can't pull off something grand, try to do something small in the best way you can do it.